Nigeria's Political Third Force, from 1960 to Peter Obi

The rise of Peter Obi in Nigeria's last presidential election was a scenario few saw coming. His candidacy under the Labour Party banner, traditionally seen as a fringe entity, disrupted the political status quo and sparked a conversation about the viability of a true third force in Nigeria's political landscape. Obi’s campaign resonated with millions of Nigerians, especially the youth, who were disillusioned with the two dominant parties and yearned for change. His unexpected success in garnering significant support highlighted a growing desire for alternatives outside the well-entrenched duopoly of the People's Democratic Party (PDP) and the All Progressives Congress (APC).

For most of Nigeria’s politics, especially in the Fourth Republic, the contest was to determine PDP’s nominee. This was the game before the game - the one that mattered. After all, at its height after the 2003 elections, the party had the presidency and 27 of Nigeria's 36 state governorship seats. But, through a combination of fatalistic hubris and opposition consolidation, its influence whittled, and 2015 provided a truly competitive alternative and saw an opposition party win a presidential election. APC, a political merger of different regional heavyweights, was meant to represent a single alternative in the tradition of most conventional political arrangements. The idea of a third force, breaking through, has usually been a fantasy because even a strong opposition was seen as impossible earlier, until the 2023 elections when the Obi disruption happened.

But as the archives show, this is not the first time Nigerians have toyed with a third force. The past might show us the likely outcome and next steps for such a political structure.

A Protest Against the Norm

In political science, a third force is a party in a two-party-dominated political space. Conventionally, most popular democracies are between two major parties that often represent different ends of the spectrum. Think Democrats and Republicans in the U.S., Labour and Conservative in the UK, or even NPP and NDC in nearby Ghana. It is why the idea of a third force bucks convention and is often a protest against established forces, usually proposing different policies, ideologies, or approaches to governance. Leaving a big party to form a faction doesn’t automatically make you a third force even in a three-horse race, unless there is an ideological difference.

Third parties are usually seen differently in a parliamentary system, where coalitions play a crucial role. In such structures, smaller parties can hold significant influence by aligning with one of the major parties to form a government. This scenario is seen in several parliamentary democracies where a two-party supremacy is still prevalent, but where these groups represent special interests and can occasionally sway the balance of power. Understanding third forces through this parliamentary lens highlights how they can disrupt established power structures by leveraging coalition dynamics, but doesn’t do much to help us understand the Nigerian context. To do so requires a trip through history and Nigeria’s previous political republics.

A Third Force Solely in Number

From independence to the first coup in 1966, Nigeria operated the Westminster parliamentary system, owing to its British colonial history. There was a prime minister as head of government, who led the largest party in the federal legislature, and a head of state, who served as ‘president’ and approved policies. A similar model applied at the regional level, with a regional governor who was ceremonial, and a premier who led the largest party in the House of Assembly.

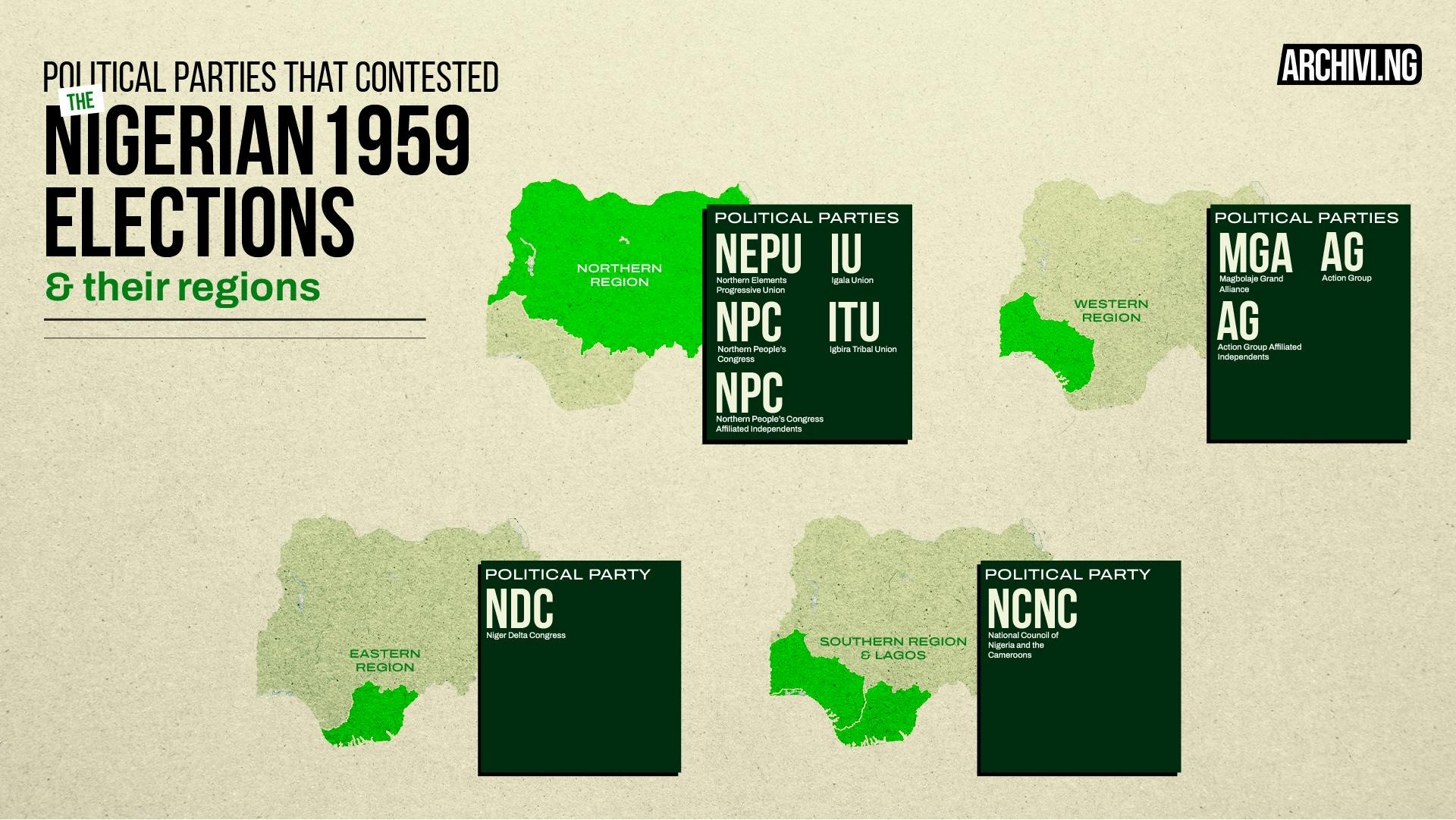

There were several political parties in early post-independence Nigeria, most of whom were formed along ethnic and regional lines. A third force was not applicable here because three strong parties were formed along the three major ethnic groups. Sir Ahmadu Bello led the North-based Northern People's Congress (NPC); Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe led the Eastern-focused National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) and Chief Obafemi Awolowo led the Action Group (AG), which was dominant in the Western region.

To establish the presence of a third force, it is important to consider the limitations of the three major parties. While all held regional power or national influence, smaller parties often represented minority ethnic interests in specific regions or on a national scale. Though these parties, such as the United Middle Belt Congress (UMBC) or the Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU), primarily operated regionally, their ability to form alliances and coalitions enabled them to exert a degree of influence. For example, NEPU’s alliance with the NCNC in the 1959 elections allowed it to win parliamentary seats that would have been difficult to secure independently. This demonstrates that while third forces may not have matched the scale of the larger ethno-regional parties, they could still play a meaningful role in shaping electoral outcomes through strategic partnerships.

The tenuous arrangement, and the ease with which losing politically could be tied to a rejection of an ethnic group, could be tied to the instability that eventually led to the military era of 1966 - 1979.

A Third Force by Structure

When Nigeria began a transition to democracy in 1978, 50 political parties were whittled down to five. Journalist and researcher, Richard Bourne, wrote of the election that “the military had tried to reduce the ethnic character of pre-war elections by insisting that all parties should have their headquarters in the national capital with branches in at least two-thirds of the states. But those precautions were inadequate.”

Awolowo re-emerged as a political force with the Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) in 1979. His party, largely Yoruba-centric, sought minority support in other regions, driven by policies centred on free education and social welfare. Azikiwe used the Nigerian People’s Party (NPP) to seek power but was soon left with a familiar Eastern-based bloc after the departure of Waziri Ibrahim, who formed the Great Nigerian People’s Party (GNPP), primarily based in the North, alongside Aminu Kano’s People’s Redemption Party (PRP), which had strong support among the northern masses (talakawa) but limited appeal elsewhere. These four parties experienced regional limitations to their electoral reach. Shehu Shagari, with the National Party of Nigeria (NPN), managed to present a more nationally inclusive front by including prominent figures from different regions, such as Alex Ekwueme and Adisa Akinloye.

In the 1979 elections, the regional nature of most parties led to a fractured political landscape, which saw the fairly national Shagari and NPN, with its strategic alliances and cross-regional representation, secure the presidency.

Despite facing strong opposition, Shagari’s NPN won the 1983 elections, primarily because other parties largely retreated into regional and ethnic politics. However, this did not entirely preclude the presence of a third force. The NPP, with its control over significant parliamentary seats and its presence in Shagari’s cabinet, emerged as a viable alternative, challenging the dominance of both the NPN and UPN. Smaller parties like the PRP and GNPP, though regionally focused, also secured notable wins, including governorship seats, which demonstrated that these third forces had influence beyond narrow regionalism. As Richard Bourne noted, the differences between these parties were often more about personalities and ethnic alignments than substantive policy distinctions. Nevertheless, these smaller parties provided crucial alternative political choices, pushing back against the idea of strict two-party dominance during this era.

However, the political landscape of the Second Republic remained heavily influenced by regional and ethnic considerations. Despite these fringe third forces, there was no fundamental shift in the power structure, with many of the political dynamics continuing from the First Republic. The persistence of regionalism suggests that these third forces were influential but did not radically alter the balance of power on the national stage.

Importantly, the shift to a presidential system in this republic introduced a "winner-takes-all" dynamic, which reshaped the political strategies of parties. In a system where 49% of the vote would result in a complete loss of power, smaller parties had little incentive to pursue national influence independently, instead seeking coalitions or accepting political appointments within larger parties. This system created conditions where third forces could exist, but they often did so through influence rather than direct competition for the presidency. And usually, they got absorbed into the bigger duopolies. While third parties like the NPP had some leverage, their role was more about exerting influence within the system rather than mounting a direct, consolidated challenge to the two dominant parties. In this context, the absence of true consolidation within the party system left room for third forces, but the structure of the republic, particularly the presidential model, ultimately limited their potential for radical change.

Soon after, the Third Republic, culminating in the much-documented June 12, 1993 elections, saw only two parties registered - the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the National Republican Convention (NRC). The 1993 presidential election, widely regarded as one of Nigeria's fairest, ended in controversy due to its annulment, precipitating the shortest republic in Nigerian history. The election featured two dominant candidates: Moshood Abiola of the SDP and Bashir Tofa of the NRC, both of whom were supported by the military regime of Ibrahim Babangida. The two-party system mandated by the military effectively nullified the third force debate. The election's annulment led to significant unrest and a prolonged period of instability, eventually leading to the fall of Babangida’s regime and the rise of Sani Abacha’s military dictatorship.

This period marked a significant setback for the concept of a third force in Nigerian politics, but not for Nigeria’s democracy itself. The dominance of the two main parties and the eventual annulment of the election highlighted the challenges of establishing a viable third force in a heavily controlled and polarised political environment. The legacy of the Third Republic in this context is one of missed opportunities for genuine political reform and a reinforcement of the two-party dominance, which persisted until the return to civilian rule in 1999. The annulment underscored the difficulty of breaking through entrenched political structures, leaving a lasting impact on the discourse surrounding third forces in Nigerian politics.

A Third Force by Longevity

When Nigerians returned to democracy in 1999, there were three major parties, laying the ground for a potential third force. But this quickly consolidated into a dominant PDP and parties that increasingly split, merged and contended regionally in the face of a relentless federal government.

The Alliance for Democracy (AD) and All People's Party (APP) (which eventually became Muhammadu Buhari’s ANPP) attempted to challenge this dominance but were unable to establish a significant third force. Despite forming a coalition in 1999, these parties remained regionally focused and could not break the PDP’s stronghold due to the ethnic and regional positioning of their parties, which the PDP had managed to move away from.

In the 2003 and 2007 elections, the PDP maintained its dominance, with the emergence of new contenders like Buhari’s All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP) and Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu’s All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA). These parties repeated the decades-long error of opposition parties as they represented ethnic or regional interests and lacked the national spread to rival the PDP effectively. The Action Congress (AC) in 2007 attempted to present itself as a viable opposition but failed to gain nationwide support due to internal and external challenges.

The 2015 elections saw the formation of the All Progressives Congress (APC) through a merger of several opposition parties. This new coalition successfully challenged the PDP, marking a significant shift in Nigeria's political landscape. Buhari’s victory was the first time an incumbent president was defeated. APC’s ability to unify various opposition groups demonstrated the potential for a well-organised opposition to challenge entrenched dominance.

The 2019 elections reaffirmed the APC's stronghold with Buhari’s re-election. The presence of multiple new aspirants from various parties, such as Omoyele Sowore of the African Action Congress (AAC) and Kingsley Moghalu of the Young Progressives Party (YPP), highlighted growing public interest in alternatives to the APC and PDP.

The struggles of Sowore, Moghalu, and other third-force aspirants in the 2019 election can be attributed to several key factors. First, their lack of a truly national profile hindered their ability to connect with the broad and diverse electorate needed to challenge Nigeria’s dominant political parties. While both candidates garnered some attention among the educated urban youth, their reach remained limited to specific demographics, failing to extend across Nigeria’s complex regional and ethnic lines. This lack of widespread recognition made it difficult for them to build a voter base that could meaningfully compete with the APC and PDP.

Another critical issue was their weak political infrastructure. The parties they represented were relatively new and lacked the organisational depth needed to mount a serious nationwide campaign. Without the resources, networks, and structures necessary to compete on a national level, their campaigns struggled to gain momentum beyond social media or niche groups.

Additionally, the inability of these candidates to form a unified opposition front further diluted their efforts. Despite a shared dissatisfaction with the APC and PDP, their fragmented approach split the vote among smaller opposition groups, preventing any single candidate from consolidating enough support to pose a credible threat.

In contrast, the 2023 elections saw a different kind of third force emerge—one that was able to break through these challenges. Obi’s third force benefited from established political capital, as well as a party with a fairly stronger national structure, allowing achievement of what had eluded previous third-force contenders: weighty momentum.

Peter Obi and the 2023 election

The 2023 elections were a pivotal moment in the country's political landscape, revealing both the potential and challenges new political actors face. The election underscored a growing discontent with the two dominant parties—APC represented by eventual winner, Bola Tinubu, and PDP represented by serial contender, Atiku Abubakar—and highlighted the emergence of alternative candidates who sought to challenge the traditional political order. As with other elections, the ‘fate’ of a third force was with candidates close enough to have some political clout but distant enough to stand apart from established political actors. At the 2023 polls, that fate was in the hands of Peter Obi of the Labour Party (LP) and Rabiu Kwankwaso of the New Nigeria People’s Party (NNPP), representing a shift towards a more pluralistic political environment.

Obi’s campaign was emblematic of this shift. His focus on economic transformation, anti-corruption, and social justice resonated strongly with younger voters and those disillusioned with the existing political elite. Despite not winning the presidency, Obi’s performance, securing 26.10% (10% lesser than the winner) of the votes, and his significant support base across regions, including winning in Lagos state and FCT Abuja, demonstrated a tangible challenge to the APC-PDP duopoly. This marked a notable departure from past elections where third forces struggled to make a substantial impact. On the other hand, Kwankwaso’s candidacy for the NNPP (6.40% of total votes cast) was not as prominent as Obi’s but still indicated a growing appetite for alternatives beyond the traditional parties. Kwankwaso’s strength as a regional powerhouse helped him win overwhelmingly in Kano state but hindered him from being a third-force candidate by our metrics of difference from the established norm and national support beyond one’s region. If he overcomes those hurdles, then he may become a third-force candidate at the next polls.

Obi’s campaign effectively harnessed social media and grassroots mobilisation, reflecting a broader desire among Nigerians for a new political direction. The emergence of the third force through Peter Obi in the 2023 elections suggests a potential realignment in Nigerian politics, where alternative parties and candidates are gaining traction. This could signal a significant shift in the political landscape, moving towards a more competitive and diverse political environment.

However, the thing with momentum is that they have to be sustained. Historically, maintaining momentum has been easier for direct oppositions than third-force candidates, as third-force potentials typically get absorbed by the larger parties.

Which Way for a Third Force?

The 2023 Nigerian presidential election was a landmark event that showcased the dynamic and evolving nature of the country's political landscape. The emergence of Obi as a credible third-force candidate highlighted the electorate's desire for new leadership and alternative political solutions. While APC and PDP continued to dominate the political scene, the strong performance of the Labour Party indicated a potential realignment in Nigerian politics.

The current internal struggles within the APC indicate the broader instability that both the ruling party and PDP will face as they gear up for the 2027 elections. The necessity to forge new alliances while keeping old ones intact will become even more critical, with both parties trying to consolidate their power bases. The possibility of Peter Obi returning to PDP or Kwankwaso joining APC looms large, casting doubt on the sustainability of any third-force momentum. Historically, such shifts have weakened the resolve of alternative movements, pulling them back into the fold of the duopoly. This risk is heightened by the Labour Party’s internal fractures, which could divert Obi’s focus from the national stage to managing intra-party conflicts, further eroding the potential of a lasting third force.

A recurring challenge with evaluating third forces is how sustainable their movements are. Many tend to wither away after a single election and reinforce the fear, by voters, that supporting these alternatives is a wasted and ultimately futile effort. For instance, if we add the caveat of these structures persisting beyond a single electoral cycle, then there have been only two third forces - Azikiwe’s NPP, which was probably down to the politics of that era, and AC/ACN which eventually merged with Buhari’s Congress for Progressive Change (CPC) and factions of other established parties to prove insurmountable.

It brings a final worry - that third parties, seeking the power to actually make a change, are eventually resigned to merging or joining establishment parties. And this ends up dousing momentum and reinforcing established duopolies. Kwankwaso—a third-force potential—for example, has been a member of APC and PDP in the past, and any further association would likely diminish the promise of a genuine alternative from his end. The institutional inertia that reinforces the dominance of a duopoly, in this case, APC and PDP, makes it difficult for any third force to easily dislodge them. Political survival often dictates compromise, and these compromises can dilute the ideological purity and independence that third forces need to sustain themselves. It is not unlikely that Obi will return to PDP and realign with the duopoly.

Does Nigeria need an alternative? That question is answered every four years. Last year, the answer was clear with support for the two main parties reaching historically low numbers and allowing a third force to gain momentum. As preparations for the next elections advance, it won’t be surprising to see new party coalitions and changes. However, if Nigerians continue to support more third force voices, then it hopefully sends a message to politicians that a failure to serve is no longer a privilege for leaders.

A game of thirds

Who finished third in every Nigerian election since 1979?

Credits

Editor: Afolabi Adekaiyaoja

Copy Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Director/Illustrator: Kehinde Owolawi