The Year Nigeria Could Not Celebrate Independence Day

When Wing Commander J.P. Alaboson took off from the Lagos airport on Saturday, September 26, 1992, Nigeria was in a celebratory mood, days away from a 32nd Independence Day anniversary.

Africa's most populous nation became a newborn of sorts when it broke loose of British shackles on October 1, 1960, and welcomed every new birthday with the extravagance Nigerians have become so well known for.

Every anniversary, a national public holiday, is filled with festivities, starting with the president's speech, followed by ceremonial events including colourful parades across the country. This ceremony—and the attendant air of national joy that rides with it—is expected to happen without fail every October 1 anniversary in Nigeria. But the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, the military transport plane piloted by Alaboson and Wing Commander A.S. Mamadi, changed things in 1992.

The Lockheed Aircraft Corporation designed the four-engine turboprop plane to be versatile—useful for a search and rescue operation as much as for an airborne assault. Originally designed as a troop, medevac, and cargo transport aircraft, it is also effective for scientific research support, weather reconnaissance, and aerial firefighting—a jack of all trades.

The C-130 Hercules entered service in the United States in 1956 and quickly enjoyed patronage from the global community. The Nigerian Air Force started buying the planes after a bloody civil war between the Federal Government and the secessionist Republic of Biafra ended in 1970.

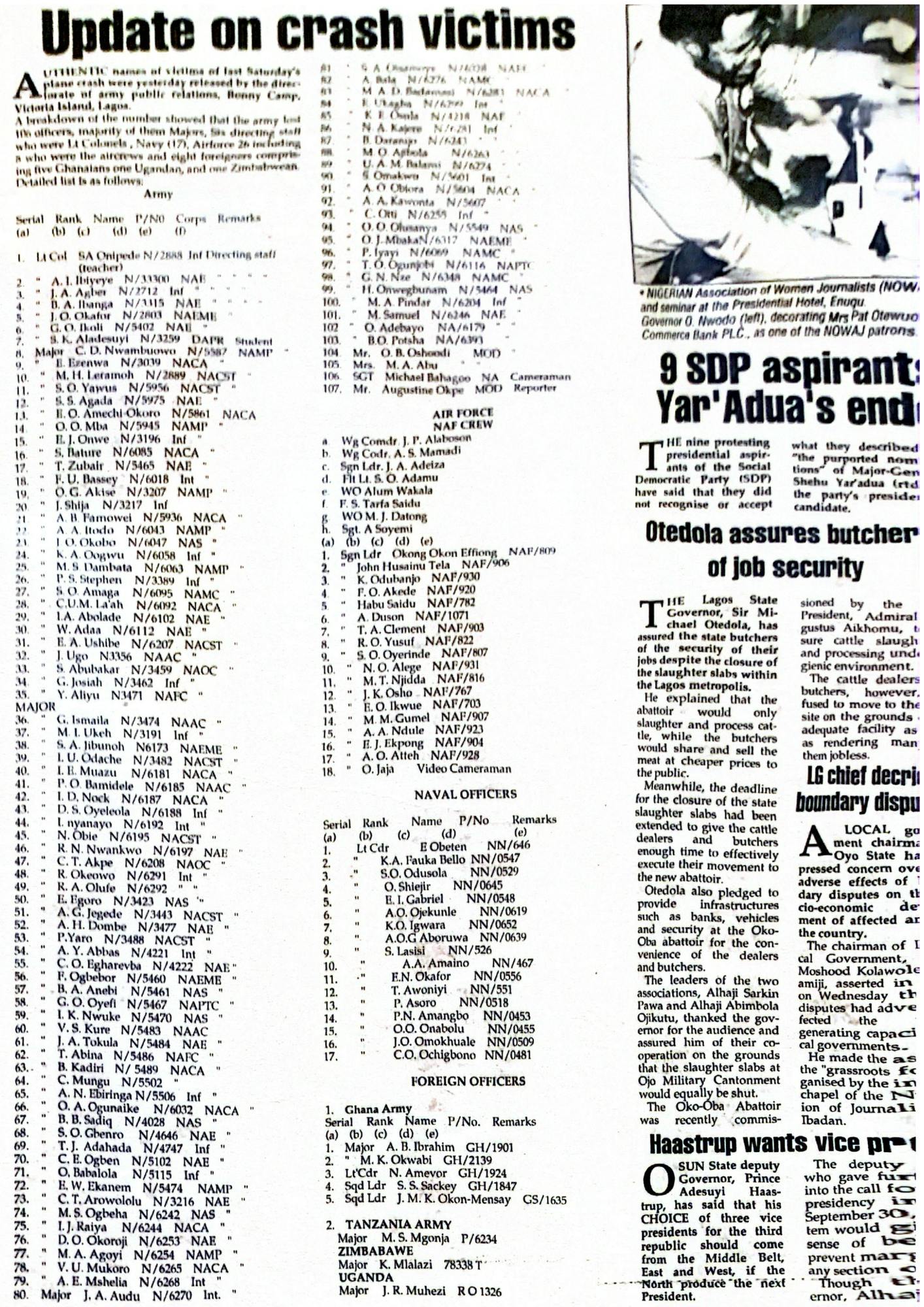

Decades later, on September 26, 1992, one of those planes, with registration number NAF 911, was carrying 160 people—there could have been more, depending on who you ask. Many passengers were middle-ranking officers in the Army, Navy and Air Force heading back to the Staff Command College in Jaji, Kaduna State. They had been on a tour of naval installations in Lagos as part of a senior division course. On the plane were also two senior staff of the Defence Ministry, and a civilian reporter who worked for the ministry. Foreigners onboard included five military officers from Ghana, and one each from Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

A Daily Times report, published on October 3, 1992, regarded Alaboson as a "seasoned pilot," so nothing was expected to go wrong when the C-130 Hercules took off around 5:30 pm from the Murtala Muhammed Airport. The pilots maintained constant communications with the control tower for three minutes before an unnerving silence ensued. And then, a crash.

The battered airplane ended up in a swamp in Ejigbo on the outskirts of Lagos, leaving a scene that horrified eyewitnesses. With the plane trapped in the muddy forest, residents used iron bars, axes, and cutlasses at the initial stages of an uncoordinated rescue operation. The government's rescue effort was significantly affected by helicopters that were not airworthy, and an ill-equipped and non-operational search and rescue centre in Lagos. Everyone onboard was killed in the crash, and a happy Independence Day anniversary became impossible.

The Ejigbo crash was a devastating blow to Nigeria's usually upbeat mood leading to the October 1 anniversary. After the head of state, General Ibrahim Babangida, visited the scene of the crash days later, he lamented that the tragedy wiped out "a whole generation of military officers."

He cancelled all planned Independence Day events. The speech was scrapped. The parades were gone. The green-white-green flags were shelved. A political forum that would have put Babangida in the same room with leaders of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and National Republican Convention (NRC) to discuss the 1993 presidential election was also disrupted.

The Guardian's October 1 publication reported that the tragedy happened amid "uncertainty in the political terrain and a general downturn in economic fortunes." The crash arrived at the worst possible time and dragged the national mood to historic lows with the number of lives lost. The military government moved an October 5 state funeral ceremony for the victims of the crash from Lagos to Abuja to press how seriously it took the tragedy.

General Sani Abacha, the Chief of Defence Staff at the time, tried to use the burial to turn the tide on the depressing national mood, urging Nigerians to attend in their numbers. "There could be no better tribute to these worthy Nigerians and officers of other countries than to actively partake in their burial ceremony," he said.

Even though the September 26 crash was one of the worst military aviation disasters globally at the time, the Nigerian government never released a report about what caused the plane to fall out of the sky. Over the decades, this has left room for whispered speculations and educated guesses: the failure of three of the plane's four engines, an overloaded flight that caused problems, and possible fuel contamination.

The crash also resurfaced the Lockheed scandal of the mid-70s when company officials admitted paying $22 million in bribes to foreign government officials to facilitate winning contracts to buy their planes. The most prominent officials at the centre of that scandal were German, Italian, Japanese and Dutch but there were whispers of Nigerian officials. Regardless of what it was all supposed to mean, the Nigerian public was denied closure on such a devastating tragedy.

By the time the next Independence Day anniversary arrived in 1993, the dark cloud of the Ejigbo plane crash had long been forgotten, overshadowed by a new crisis—Babangida's annulment of the June 12 election. The crash didn't even get a mention in the 1993 Independent Day speech delivered by Ernest Shonekan, head of the Interim National Government that took over from Babangida that August and was overthrown by Abacha a month after that year's anniversary.

Despite its very Nigerian erasure, the Ejigbo crash is the last significant event in 32 years to negatively impact a day set aside for Nigerians to rise above the despair of unrealised national dreams, praying the same prayer—for a future where things work.

Credits

Editor: Enajite Efemuaye

Art Director/Illustrator: Owolawi Kehinde

Researchers: Olalekan Ojumu