What Happened When Nigeria Kidnapped a Wanted Former Minister in London

The early hours of January 1, 1984, marked a grim beginning for Nigeria as martial music filled the airwaves, signalling the end of Shehu Shagari's presidency and the dawn of yet another military regime. As Lagos slept off its festive hangover, soldiers quietly moved into position, executing a coup that would spark a chain of events reaching as far as London—culminating in one of the most audacious political kidnappings in modern history. At the centre of it all: the elusive Umaru Dikko, Nigeria’s most wanted man.

It was Saturday, December 31, 1983 in Lagos, then the capital of Nigeria, and the city was agog with New Year’s Eve excitement. Friends and families gathered, celebrating and reminiscing on the year past, and no doubt making plans for the year ahead. But a deep collective anxiety festered just below the surface of the ritual festivity. All was not well with the country.

The past year, and indeed the years before it, had been blighted by social, political and economic challenges. Oil prices crashed drastically in 1982 due to a decline in the global demand for the product. For Nigeria, a nation whose revenues were almost solely dependent on oil, this spelt economic turmoil and precipitated a recession. Poor policy decisions by President Shehu Shagari’s federal government exacerbated the loss of oil revenues. Inflation surged, food prices skyrocketed, crime was on the rise, and the government—the nation's largest employer of labour—struggled to pay salaries. Nigerians were suffering.

As the situation worsened, the federal government predictably looked for scapegoats on which to hang the nation's woes. The government targeted many foreign workers, most of whom had come to Nigeria in response to the jobs created by the oil boom a decade prior. Early in 1983, President Shagari sanctioned an executive order to expel over two million immigrants, virtually overnight. Over half of those expelled were Ghanaian nationals, earning the exercise the now-infamous “Ghana Must Go” moniker.

Though Nigeria’s economic outlook barely improved in the following months, President Shagari won re-election in the hotly contested and controversial elections of August 1983—one marred by massive rigging and electoral malpractice.

Amid the results being challenged by opposition parties, the president’s campaign manager, Umaru Dikko, was cavalier in victory, having succeeded against political juggernauts like Chief Obafemi Awolowo and Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe. In an interview shortly after the results were announced, Dikko told reporters “Whether they [the opposition] accept or don't accept the results is immaterial.”

Three months into Shagari’s second term in office, the nation continued to endure the pangs of economic mismanagement. But while ordinary people suffered, government officials lived in luxury, unaffected by the economic turmoil they brought upon the country.

The Return of the Khaki Boys

This was the backdrop that set the stage for a coup d’etat against the government, as the military surreptitiously moved to depose Shagari’s government and seize power in the wee hours of December 31, 1983, while Nigerians slept, prayed or partied into the new year. By 9 am on the first day of the year, martial music was broadcast across television and radio stations, which could only mean one thing. Shortly after, Brigadier Sani Abacha, a member of the inner circle of soldiers responsible for the coup, confirmed what many Nigerians already suspected in a radio broadcast. Shagari’s government had been deposed for “inept and corrupt leadership, economic uncertainty and embarrassing levels of unemployment.”

Major-General Muhammadu Buhari became head of state on the back of the coup. Buhari was born in Daura in the North West (located in present-day Katsina State) on December 17, 1942, and completed his secondary education at Katsina Provincial Secondary School. In 1962, he enlisted in the fifth course of the Nigerian Military Training College (NMTC). He was commissioned into the Nigerian Army in January 1963, after which he was posted to the 2nd Battalion stationed at Abeokuta.

Buhari was considered by his counterparts in the military as disciplined, stoic and uncompromising. Based on this reputation, many Nigerians considered him the ideal leader to rein in the culture of excess created by the previous government. Historian Mike Siollun writes, “The Buhari regime came to office with tremendous goodwill. The public and press jubilantly welcomed the military’s return to politics.” The Nigerian masses had grown tired of their kleptocratic ruling class and welcomed Buhari’s promise to declare “war against corruption.” In contrast, the erstwhile political elite, comprising officials from the previous administration and their allies, were thrown into disarray, as they shifted from the apex predator to hunted prey literally overnight.

Nigeria's most wanted man

Several months had passed since the coup d’etat that brought Major-General Buhari into power. Halfway across the world, a middle-aged Nigerian man had just stepped out for his daily stroll in a quiet suburb of London. As he walked, he reminisced on the recent past. Barely a year ago, he had successfully masterminded the re-election of a sitting president. As minister of transport, presidential campaign manager, and the president's brother-in-law, he was once one of the most powerful men in the country. But here he was today, unassuming, unremarkable, stripped of all the pomp and pageantry of political office. Many of his political allies were in detention, awaiting trial or already serving hefty prison sentences for embezzlement in Nigeria. Others were scattered in exile all across Europe. The man was none other than Umaru Dikko, who fled Nigeria to avoid political persecution just a few days after his 48th birthday.

Dikko was born on December 31, 1936 in Wamba, Kaduna State. He obtained a BSc degree in Mathematics from the University of London and afterwards worked for the BBC’s Hausa service, expanding his influence as a thought leader in regional and national politics. From the late 1960s, Dikko held several positions in government, including commissioner for finance and commissioner for information in North Central State (now known as Kaduna State). Following Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1979, Dikko ran for and lost a seat in the Senate. He was later appointed to the post of Transport Minister by his brother-in-law, President Shagari.

In many ways, Dikko embodied the archetype of the Nigerian politician in the 1980s. He was wiley, flamboyant, aloof to his constituents and bitter to his perceived opponents. In addition to being Transport Minister, he led the infamous presidential task force set up to address food shortages by distributing imported rice. The task force was accused of hoarding rice to intentionally worsen food shortages and inflate prices. Dikko was also accused of granting import licenses only to businessmen with ties to the ruling National Party of Nigeria (NPN). In an interview with the New York Times in 1981, an opposition lawmaker, Senator Mohammed Girigiri Lawan, alleged that ''the shortage of rice is definitely contrived and promoted by a few privileged Nigerians in high positions'' for profitable speculation.

Dikko—in addition to being one of the figureheads of a corrupt and failing government, also antagonised the top brass within the Nigerian military by ordering covert surveillance on them, including the General Officer Commanding of the 3rd Armoured Division in Jos—one Major-General Muhammadu Buhari. It was therefore no surprise that once Buhari assumed power, Umaru Dikko’s name topped his regime’s list of fugitive politicians. In just his second day in office, Buhari formally accused Umaru Dikko (as well as a host of other Second Republic politicians) of a variety of crimes, most notably looting the national treasury and embezzling billions of dollars of public funds.

The Kidnap Plot

By the time soldiers converged on Dikko’s official residence at 16, Alexander Avenue, South West Ikoyi, Lagos, he had already escaped. He smuggled himself to the Republic of Benin, and then slipped on to Togo’s capital, Lomé, before boarding a KLM flight bound for London via Amsterdam.

Even in exile, Dikko remained a thorn in Buhari’s side. He quickly became an unofficial spokesperson of dissenters to Nigeria’s new military government. He appeared often on British television and granted interviews where he harshly criticised the Buhari junta, promising to put an end to the regime. All this only served to strengthen General Buhari’s resolve to get his man, exile or not.

Umaru Dikko’s kidnap and the entire affair afterwards sounds like something out of a Cold War-era spy novel. The plot to capture Dikko and bring him home to face trial was a collective effort, devised by the office of the head of state in liaison with the National Security Organisation (NSO), and with assistance from Israel’s elite secret service: Mossad.

The first step was to locate Dikko’s hideout. Both the NSO and Mossad deployed scores of undercover agents and covert operatives to gather intelligence about his whereabouts. On June 30, 1984, a Mossad operative spotted someone matching Dikko's description in London's upscale Bayswater neighbourhood. For several days, agents kept the house under constant surveillance, closely monitoring Dikko's routine and movements.

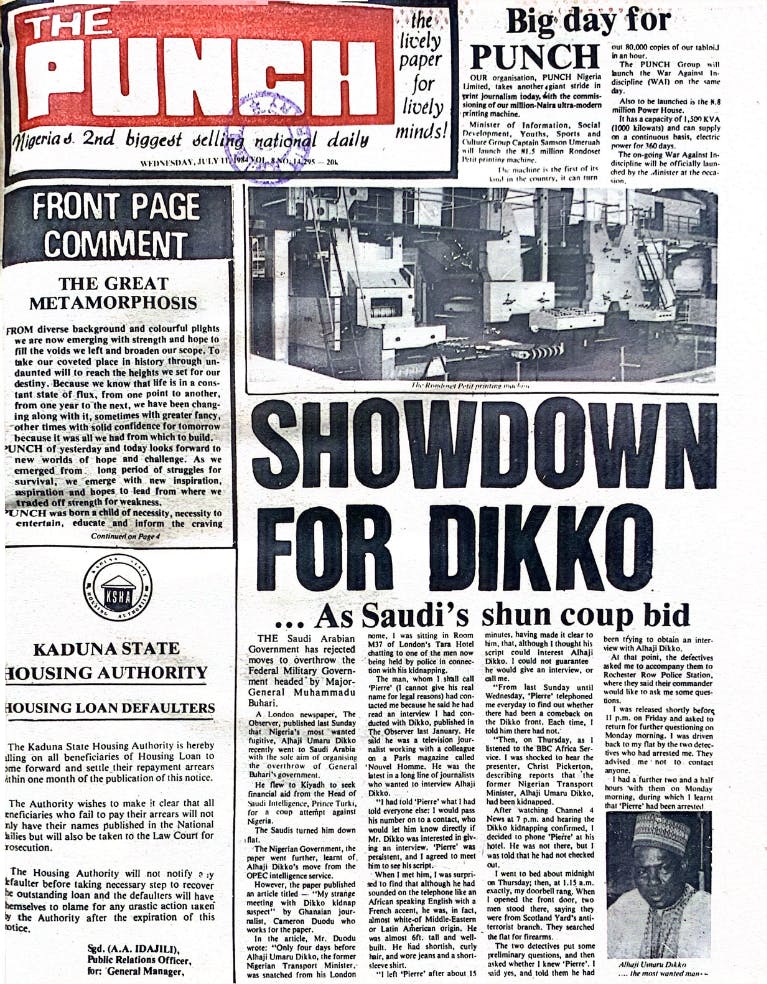

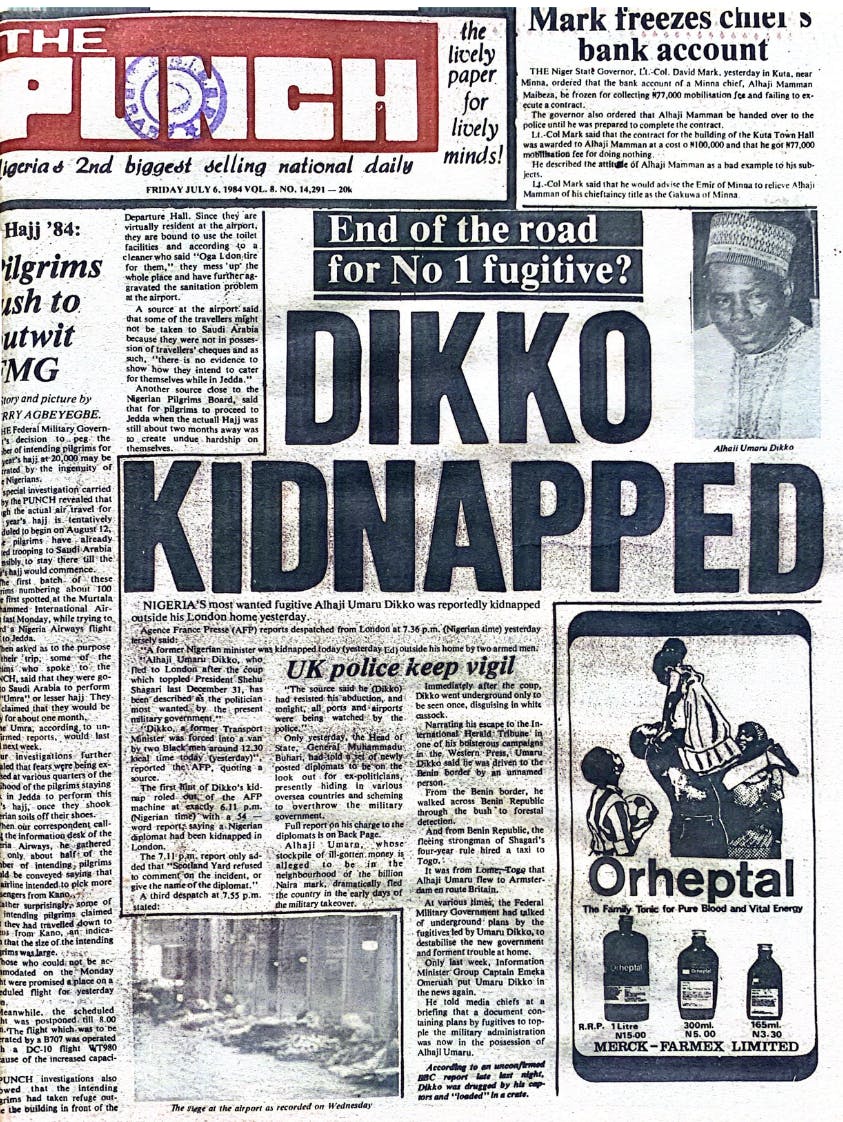

On July 5, 1984, shortly after midday, Dikko emerged from his house to take a stroll before lunch. He was assailed by two men who grabbed him, bundled him into a van, and zoomed off. After several minutes of navigating London’s bustling streets, the van stopped and Dikko was transferred to a waiting truck. There, he was injected with a powerful respiratory depressant, rendering him unconscious.

Around 4 pm, a van escorted by two black Mercedes Benz cars with Nigerian diplomatic license plates drove into Stansted Airport in Essex. They were ferrying two large crates, referred to as "diplomatic cargo" to avoid any checks. Before the crates could be loaded onto a waiting Boeing 707 aircraft, a British customs officer named Charles Morrow noticed an unusual smell coming from one of the crates and insisted on taking a closer look. Even though diplomatic packages were protected by the Vienna Convention and should not be searched by customs, the crates were not appropriately marked 'diplomatic bag.' Morrow, recounting the story in an interview with the BBC, said, “The day had gone fairly normally until about 3 pm. Then we had the handling agents come through and say that there was a cargo due to go on a Nigerian Airways 707, but the people delivering it didn’t want it manifested.”

Among “the people delivering it” was Major Mohammed Yusufu, a 40-year-old former Nigerian Army officer turned diplomat, as well as another member of the Nigerian High Commission in London named Okon Edet. Murrow continued, “Just then a colleague returned from the passenger terminal with some startling news. There was an All Ports Bulletin from Scotland Yard saying that a Nigerian had been kidnapped and it was suspected he would be smuggled out of the country.”

Unbeknownst to Dikko’s assailants, there was a hitch in their perfectly laid plans. Dikko’s secretary, Elizabeth Hayes, had witnessed his abduction through a window. She alerted the police, and revealed Dikko’s status as a former Nigerian government minister. The news quickly circulated across other security agencies. The chief of Scotland Yard’s anti-terrorist squad, Commander William Hucklesby was alerted, as was the UK Home Office and even the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Though Murrow suspected something fishy, nothing could have prepared him and the other security agents present for what they would see when they forced the crates open. In the first crate, arms and feet bound, naked from the waist up and unconscious with a tube in his throat was Umaru Dikko. His abductors had inserted an endotracheal tube into his throat to prevent him from choking on his own vomit while unconscious. Beside him was a man with a reserve supply of syringes and anaesthetics, apparently keeping him alive but sedated and ready to administer more medication if necessary. The man was later identified as Dr Levi-Arie Shapiro, a 43-year-old Russian-born Israeli national, a consultant and director of the intensive care unit at Hasharon Hospital, Tel Aviv, and a reserve Major in the Israeli army. In the second crate were Dikko’s abductors; 31-year-old Tunisian-born Israeli national, Felix Masoud Abithol, and Alexander Barak, a 27-year-old Israeli national who worked for the Israeli intelligence corps after completing his military service.

Following the discovery, Dikko was rushed to Hertfordshire and Essex Hospital in Bishops Stortford, and only regained consciousness the following day, having been unconscious for nearly 36 hours.

Diplomatic Fallout: Britain vs Nigeria

It was only after the plot failed that the Nigerian government filed a formal extradition request for Dikko and other Nigerian politicians in exile. Their request was rejected. Her Majesty’s government did not react kindly to the kidnap attempt on its soil and regarded the involvement of Nigerian security agencies and foreign affairs commission as an act of extreme hostility.

The British Parliament debated the matter on July 12, 1984. One Member of Parliament, George Robertson, summed up public sentiments on the issue; that the British government needed to “make it clear that this country will not, in any circumstances, allow the import onto our streets of other countries' quarrels, whether or not covered by diplomatic immunity. The message from this country and the House to the Nigerians or to anyone else who is aggrieved must be this: use courts, not crates.”

The Nigerian Airways aircraft 707 was grounded, and 17 people in total were arrested on suspicion of involvement in Dikko’s kidnap, including the Boeing 707 crew, Shapiro, Abithol, Barak, Yusuf and Edet.

The Nigerian government continued to deny knowledge or involvement in the plot. The official reaction from Nigeria’s High Commissioner in London, Major-General Haladu Anthony Hannaniya was that the incident was the work of “some patriotic friends of Nigeria.” The Nigerian government played a game of tit-for-tat, ordering a British Caledonian Boeing 747 flight that had taken off from Lagos 45 minutes earlier, back to the airport “for security reasons.”

The British Foreign Secretary, Geoffrey Howe, escalated the situation by expelling Oyedele and Edet, the two Nigerian High Commission staff arrested during the investigation. Nigeria reacted by also expelling the British High Commissioner in Lagos, Hamilton Whyte, and two diplomats of the British High Commission in Nigeria.

During the debacle, General Buhari released a statement, saying, “Britain, which has been for so long regarded by Nigerians as a traditional friend, has caused us once again in recent times to doubt the genuineness of this friendship. Today as Nigeria faces the test of economic survival and the maintenance of its national unity and stability, Britain is once again sitting on the fence…”

Diplomatic relations between the two countries went completely sour after the Umaru Dikko affair and ceased completely until 1986, the year after General Buhari was sacked from office in a coup instigated by his Chief of Staff, General Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida.

The Aftermath

Four of the original 17 suspects—Barak, Shapiro, Abithol, and Yusufu—were tried at London’s Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey. The Israeli and the Nigerian governments continued to distance themselves from any official state involvement, and the defendants claimed they were mercenaries working for Nigerian businessmen. They were all pronounced guilty and sentenced to various prison terms, ranging from 10 years to 14 years. All the convicts were freed after serving more than half of their sentences, and deported to their respective nations of origin. High Commissioner Major-General Haladu Anthony Hananiya who was also expelled from Great Britain, would admit decades later in his memoir “All Eyes on Me” that the Nigerian government was indeed involved; claiming that though he did not have personal foreknowledge of the plot, he had to defend his country by sticking to the official story.

Umaru Dikko made a full recovery but remained in the United Kingdom for years after the abduction. He later married Hayes, the personal secretary who raised the alarm about his kidnap. He returned to Nigeria in 1995 after assurances from General Sani Abacha, who ironically was part of the government that tried to kidnap him a decade earlier.

Nigeria would return to democracy again in 1999 following the election of President Olusegun Obasanjo. One of his first acts in office was to establish a seven-member panel to investigate human rights abuses under past military governments. Dikko, still resentful about his treatment during Buhari’s regime, sponsored a petition against those he believed were responsible for his ill-treatment. In an impassioned plea, he complained to the panel, “Up to this day, the Nigerian government of that time or of any other time never admitted involvement in this international crime, despite the fact that evidence of involvement was overwhelming…nobody has bothered to say "Sorry" let alone to clear my name of all those lies heaped upon me, not to talk of material compensation. My political career has been ruined and yet no guilt of any crime has been proved. My family's name is soiled and anywhere I go people seem to still think they are looking at Umaru Dikko, the man who took billions from Nigeria.”

Dikko went on to hold minor administrative roles within the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) until he died from an illness on July 1, 2014, in London.

Credits

Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Director/Illustrator: Owolawi Kehinde

Researcher: Olalekan Ojumu