Why Ken Saro-Wiwa Kept Fighting for His Environment

General Sani Abacha carried many titles beyond ‘Head of State.’ He was called a murderer, kingpin, thief, and many other things you have probably heard. After all, he is one of Nigeria’s most infamous dictators.

I was born in 1999, so I completely missed the Abacha years in Nigerian history—lucky me—but the people who lived through it cannot forget. People like my grandmother. Growing up, listening to her tell stories about Abacha always felt like watching a horror film. But a particular story sticks to me through the years.

On November 10, 1995, the Abacha junta executed Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other activists. The story of Saro-Wiwa’s death is one of the most well-known touchpoints in Nigerian history, but there was more to his life.

Who Was Ken Saro-Wiwa?

Ken Saro-Wiwa was many things to different people: a patriot, an Ogoni nationalist, father of the African environmental movement, writer, poet, essayist, playwright, and TV producer.

Based on his novel, Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English, which explores the growth and loss of innocence during the Nigerian Civil War, I would call him a writer-activist. Saro-Wiwa was a political columnist in Nigeria’s premier newspaper, the Daily Times, using his column as a medium to challenge the exploitative oil companies, the plight of the minority ethnic groups in Nigeria, and the environment.

“Week after week, I made sure that the name Ogoni appeared before the eyes of the reader. It was a television technique, designed to leave the name indelibly in their minds.”

Saro-Wiwa stood against the Nigerian government's willful negligence of the damaging, and even criminal activities of oil companies in the Niger Delta. In 1994, a Swedish foundation awarded him the Right Livelihood Award, often referred to as the “Alternative Nobel Prize,” for his activism.

I was always baffled about why someone like him was killed, and I quickly found my answer once I dug into the recorded accounts of the time.

To General Sani Abacha, Ken Saro-Wiwa was a thorn in the flesh, so he needed to become a murderer.

The Ogoni Struggle

As a voice for the marginalised people of the Niger Delta, Saro-Wiwa founded the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) in 1990. His leadership was instrumental in transforming MOSOP into a powerful platform that demanded environmental restoration, fair revenue distribution, and political autonomy for the Ogoni people.

In the Ogoni Bill of Rights, published in 1990, the group detailed the Ogoni grievances and called for self-determination. The document condemned Abacha’s government and Shell for their exploitation of Ogoniland while demanding reparations for environmental damage and a fair share of the revenues generated from oil extracted from the region.

Through his activism and MOSOP, Saro-Wiwa brought international attention to the environmental abuses and human rights violations occurring in the Niger Delta under the Abacha military regime. As a result, global pressure mounted, and Shell's brand image began to suffer due to its association with environmental degradation and social injustice.

Abacha responded to the growing unrest with violent repression by heavily militarising the Ogoni region, spearheading a campaign of intimidation, harassment, and brutality against Ogoni activists. To break MOSOP’s influence and halt its momentum, the military dictator targeted the activist.

In May 1994, armed soldiers arrested Saro-Wiwa, Saturday Dobee, Nordu Eawo, Daniel Gbooko, Paul Levera, Felix Nuate, Baribor Bera, Barinem Kiobel, and John Kpuine. They were known as the Ogoni Nine.

The Trial of the Ogoni Nine

The special tribunal that tried the Ogoni Nine operated under a decree that ensured its decisions were beyond the scrutiny of Nigeria’s regular judicial system. The tribunal was chaired by Justice Ibrahim Auta, a judge widely seen as aligned with the regime’s interests.

The tribunal also consisted of military and civilian officials chosen by the regime, and the prosecution's case was strongly supported by the government, while the defence faced systemic harassment. Defence lawyers were frequently obstructed, intimidated, and denied critical opportunities to present evidence. Amnesty International and other human rights observers described the tribunal as a sham trial, specifically tailored to crush dissent and eliminate MOSOP’s leadership.

The charges centred on allegations that Saro-Wiwa and his co-defendants had incited the murder of four prominent Ogoni chiefs—Edward Kobani, Theophilus Orage, Samuel Orage, and Albert Badey—during a community dispute. However, the prosecution’s case relied almost entirely on coerced testimony.

Witnesses who testified against Saro-Wiwa later admitted they had been bribed by government agents, with promises of money and jobs, to implicate him. No physical evidence or reliable testimony directly tied the defendants to the murders. The absence of substantive proof reinforced the argument that the charges were fabricated as a pretext to silence the activists and suppress the growing momentum of the Ogoni struggle.

On October 31, 1995, the special tribunal delivered its judgement, sentencing the Ogoni Nine to death by hanging. The verdict had been widely anticipated, as the tribunal’s proceedings had already demonstrated its bias. The judgement left no room for appeals due to the military decree under which the tribunal operated.

Interestingly, while the nine activists were condemned, six co-defendants were acquitted of the same charges. This was perceived as a calculated move by the regime to create the illusion of impartiality while ensuring the elimination of the most influential MOSOP leaders. The tribunal’s verdict was immediately referred to the Provisional Ruling Council (PRC), Nigeria’s highest decision-making body under the military regime, for consideration.

In a memo to PRC members who ratified the judgement, Abacha clearly expressed support for the swift execution of the Ogoni Nine. The dictator told the council not to show any sympathy to the convicts so that they would serve as a lesson to anyone embarking on civil disobedience in Nigeria.

The PRC reflected an uncompromising stance on dealing with the Ogoni movement. The junta viewed their activism as a serious threat to national unity, dismissing international condemnation as irrelevant. The council described Saro-Wiwa as a foreign agent used to destabilise Nigeria, and a separatist who cloaked himself as an environmental activist. Abacha and council members were determined to take swift action to avoid appearing weak, even if it meant disregarding legal norms.

Despite the global outcry to stop the execution, the Abacha regime carried out the hanging of the Ogoni Nine to the world’s horror.

“Whether I live or die is immaterial. It is enough to know that there are people who commit time, money and energy to fight this one evil among so many others predominating worldwide. If they do not succeed today, they will succeed tomorrow.”

Ken Saro-Wiwa’s final words.

International Isolation, Sanctions and Suspension

Even Abacha himself could not have foreseen how a singular event would upset his government’s standing in the global community. In the days following the execution of the Ogoni Nine, wild protests erupted across major cities of the world. From London to New York, demonstrators picketed Nigerian embassies, chanting slogans in support of the Ogoni cause.

Memorials were held, and protests and campaigns demanding justice for the Ogoni Nine gained momentum. International organisations that had previously paid little attention to the human rights violations associated with the oil industry in Nigeria could not turn a blind eye anymore.

Unfortunately for Abacha, the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) was taking place in New Zealand at the time of the executions. The group immediately suspended Nigeria's membership, an unprecedented move. The following month, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that condemned Nigeria for the execution of the Ogoni Nine. The UN encouraged member-states to impose their own sanctions, hoping Nigeria would restore democratic rule.

The European Union (EU) also introduced sanctions, adding to earlier measures imposed after the annulled 1993 elections. The European Parliament and the ACP-EU Joint Assembly—a group of European Parliament members with African, Caribbean, and Pacific representatives—repeatedly advocated for an oil embargo on Nigeria during Abacha’s rule.

By the late 1990s, the combination of economic hardship, diplomatic isolation, and internal resistance culminated in an unsustainable situation for the Abacha regime. The dictator started laying the groundwork for a democratic transition—which still put him at an unfair advantage—when he suddenly died in 1998. That twist particularly created an opportunity for political change. His successor, General Abdulsalami Abubakar, quickly initiated plans for democratic elections, recognising that military rule was no longer viable without risking further economic collapse and international isolation.

A Parallel of Two Worlds

Nigeria's current freedom of expression under democratic civilian rule is a reflection of both progress and persisting challenges. The #EndSARS protests of 2020 that ended with the Lekki Toll Gate shooting of unarmed protesters underscore pressing concerns about freedom of expression, police brutality, and state accountability in Nigeria.

These issues remind us of the repression experienced by Saro-Wiwa and his supporters in the 1990s. What both events prove is the existence of a troubling pattern in which the Nigerian government resorts to forceful suppression of dissent.

Much like in Saro-Wiwa’s era, where he was framed as a threat to national stability, the government’s response to the #EndSARS protests, and other acts of civil disobedience over the years, demonstrated a resistance to acknowledging or addressing systemic abuses within its institutions. This culture exposes how Nigerian authorities prioritise control over transparency, employing military force to suppress civil movements that challenge state practices.

Saro-Wiwa’s execution under Abacha’s military regime exemplified the harsh measures taken to silence dissent, while the Lekki shooting exposed similar tendencies within a democratic framework, questioning the state’s commitment to protecting the rights of its citizens.

Legacy of a Martyr

Ken Saro-Wiwa’s life, advocacy, and ultimate sacrifice have left a mark on Nigeria's civic consciousness. At the end of his trial, the special tribunal prevented the activist from reading a prepared speech—a statement intended to explain his unrelenting fight against the rampant injustices of his time.

Through his words and actions, Saro-Wiwa fought to awaken the world to the systemic oppression he refused to let go unnoticed.

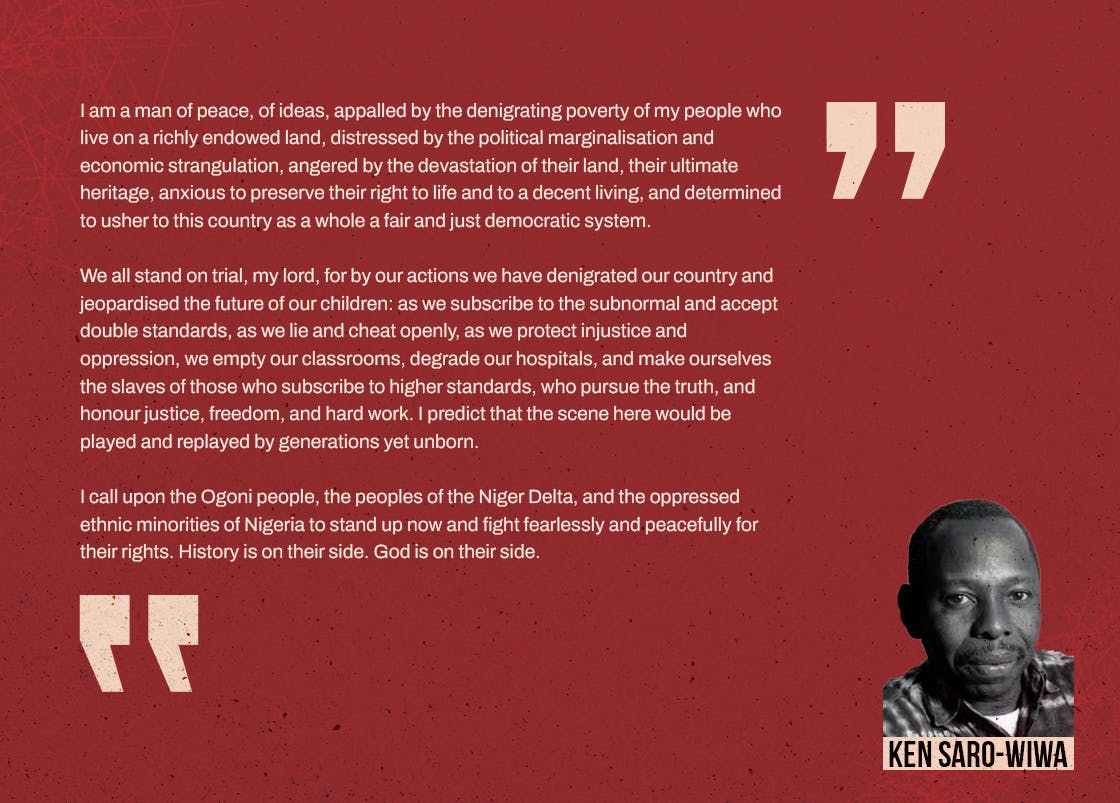

Here is an excerpt of what he planned to say.

Credits

Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Illustrator/Director: Owolawi Kehinde