Mojekwu v. Mojekwu: Nigerian women's generational fight for inheritance

When Okechukwu Mojekwu died in 1944, his wives—Caroline and Janet—and two daughters could not inherit his property.

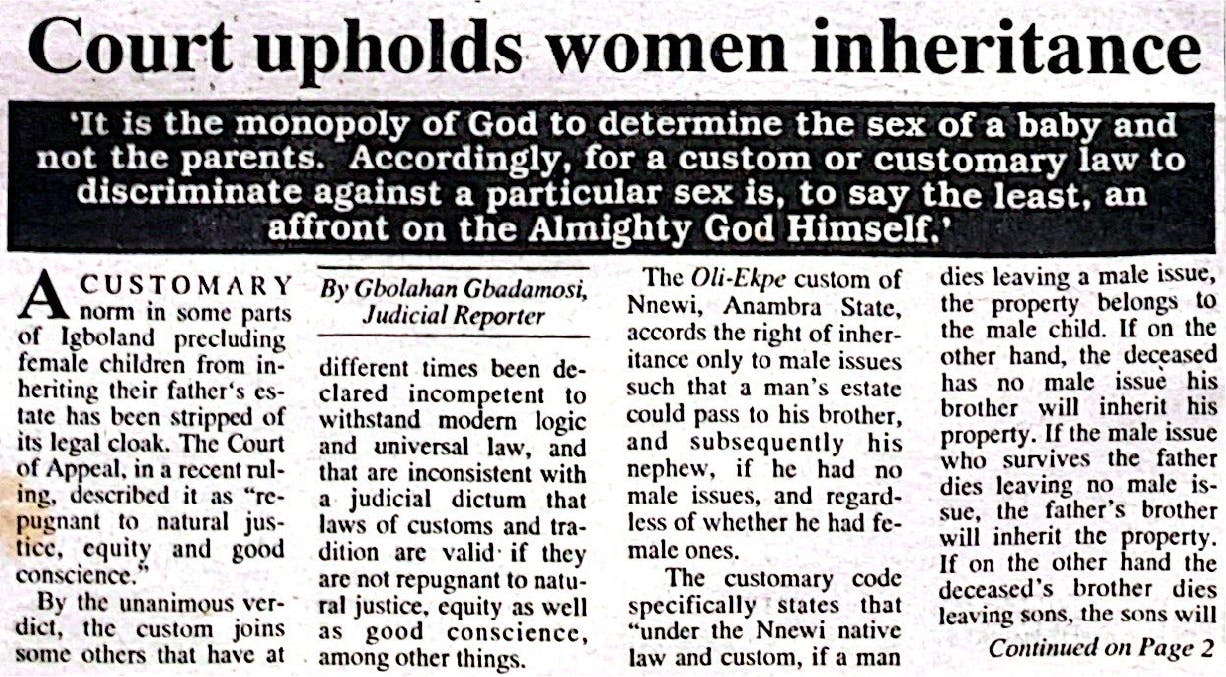

The Oli Ekpe custom of his Nnewi hometown granted the right of inheritance to only male heirs, like a son, or men in the extended family. This leaves room for a dead man's property to pass to his brother, and further to his brother's son, called the Oli Ekpe, before it would ever pass to his wives or daughters.

Okechukwu had a son with Caroline named Patrick Adina so his property stayed within his immediate family. But Patrick died during the Nigerian Civil War of the late 1960s, unmarried and without an heir. By then, Okechukwu's only brother, Charles, was also dead. But he was survived by his son, Augustine, who was now the heir to Okechukwu's estate. As the eldest male of the Mojekwu family, he was the Oli Ekpe.

Igbo Women v. Inheritance

In Ugboma v. Ibeneme (1967), a Nigerian court ruled that daughters in Igbo land had no right to inherit land from their fathers. Many Igbo customs determine inheritance by male primogeniture, and a woman’s sole entitlement is “maintenance” until she marries, becomes independent or dies. Even this is conditional on “good behaviour.”

The argument for the custom was that Igbo land was largely communal, and “a girl child belongs to another family.” As a result, it was considered taboo to bequeath an estate to a woman, whether married or unmarried, daughter, wife, or sister.

"Female children are not entitled to inherit from their father’s estate in Igbo land. If a man who is subject to Igbo customary law dies intestate without any male issue, his property will be inherited by his brothers to the exclusion of his female children."

Ugboma v. Ibeneme

This judicial position resurfaced in the 1972 ruling of Ejiamike v. Ejiamike, where Justice Chukwudifu Oputa held, “A widow of a deceased person had no right under Onitsha customary law to administer the estate of her late husband.”

For generations, the Nigerian judiciary was reluctant to declare the principle of exclusive male right of inheritance as discriminatory, but women never stayed silent about it.

Mojekwu v. Mojekwu

Before Okechukwu died, he acquired land from the Mgbelekeke family in Onitsha under the 1935 Kola Tenancy Law which granted him customary tenancy—with all the rights of an owner, except that he could not sell. When Augustine inherited the house the deceased built on the property and paid the kola required to the Mgbelekeke family, Okechukwu's two daughters signed the docket of consent as witnesses.

Months before the end of the civil war, Augustine allowed Caroline and one of Janet’s daughters stay in the Onitsha house. He also allowed Caroline to collect rent from tenants. But when she started moulding cement blocks on the property in preparation to construct a building, Augustine was upset she did not get his consent first. To address the violation of his role as head of the family, he made a public announcement in newspapers warning prospective renters to keep off. In 1983, he sued Caroline.

In court, she argued that when the house went into ruins after the war, she rebuilt it with her own money and put in all rent-paying tenants. She also argued that Augustine had not actually inherited the property under Oli Ekpe custom. As proof, she brought up two previous court cases she had won regarding the property. The first one was a suit she won in 1959 when Okechukwu’s relative tried to take the property from her whilst Patrick was still alive. The second one, decided in her favour in 1982, gave her the right to evict Augustine’s associate, who had occupied a room illegally. In both cases, Augustine's sister, Esther Okakpu, stood as a witness for her and testified against her brother.

The high court dismissed his case but, believing strongly that he was entitled to the property as Oli Ekpe, Augustine appealed the judgement. In a 1997 ruling, the Court of Appeal in Enugu upheld the high court's decision, affirming that the general rule is that land and other immovable properties are governed by lex situs—the law of the location rather than the personal law of the deceased. In this case, that meant following the kola tenancy rules, which allowed the children of a deceased kola tenant to inherit regardless of sex, provided they paid the necessary kola dues to the Mgbelekeke family. Again, the case ended in favour of Caroline.

The strong language with which the court voided the Oli Ekpe custom was celebrated by women, as it meant discriminatory customs that marginalised them were invalidated. Caroline, who was 90 at the time, also received an award from Women Watch Africa, an NGO, for not giving up on the long fight. But the joy of the moment was short-lived.

The Guardian. September 19, 1997

Unhappy with the court’s decision, Augustine appealed to the Supreme Court, the final stop for judicial decisions in Nigeria. One of the issues he raised was that the appeal court ruled based on issues not raised or requested by either party involved in the case, which is against the rules of procedure in court.

Caroline was now dead, so Okechukuwu’s daughter with Janet, Theresa Iwachukwu, had to take over the legal battle. The case was now known as Mojekwu v. Iwachukwu. In 2004, the Supreme Court opposed the Court of Appeal’s scathing criticism of the Oli Ekpe custom.

"A custom cannot be said to be repugnant to natural justice, equity and good conscience just because it is inconsistent with an English law or some principle of individual right as understood in any other legal system."

Supreme Court of Nigeria, Mojekwu v. Iwachukwu

This judgement was a setback, but it wasn't the end, as women continued to fight against inheritance discrimination.

Become an ARCHIVI.NG member and get updates straight to your inbox

Ukeje v. Ukeje

After Ogbonnaya Ukeje died in 1981 without a will, his daughter, Gladys Ada Ukeje, was in danger of losing out on inheritance. When her stepmother, Lois Chituru Ukeje, and half-brother, Enyinnaya Lazarus Ukeje, applied for letters of administration for her dad’s estate, excluding her, it was granted. But she could not just watch this happen, so she took legal steps in 1982.

She presented documents—and her mum as a witness—to prove she was the daughter of the deceased and therefore had a right to inherit. The court recognised her as Ogbonnaya’s daughter, invalidated the former letters of administration and asked her to be included in a new arrangement. Like Augustine, the losers of the case were unsatisfied, so they appealed the judgement, but the Court of Appeal dismissed their case. They protested the judgements at the Supreme Court and got the same verdict. The court said the Igbo customary law that blocked women from inheritance conflicted with the Nigerian constitution.

"No matter the circumstances of the birth of a female child, such a child is entitled to an inheritance from her late father’s estate."

Supreme Court of Nigeria, Ukeje v. Ukeje

About eight years after the judgement, in September 2022, Rivers became the first Nigerian state to back the Ukeje judgement when Governor Nyesom Wike signed The Rivers State Prohibition of the Curtailment of Women’s Right to Share in Family Property Law.

Four sisters won an inheritance court case against their three younger brothers standing on this law the following year.

Inheritance Rights for Nigerian Women

Discriminatory customs that hinder women’s inheritance exist across different ethnic groups in Nigeria. In some Yoruba customs, a wife only has possessory rights but cannot inherit her husband’s property. The court's ruling in Sogunro-Davies v. Sogunro-Davies (1928) established that inheritance is by blood, and this position was taken even further in Suberu v. Sunmonu (1957), where the court stated that a wife is like a chattel to be inherited by her deceased husband's relative.

Under Bini native law and custom, the eldest son of a deceased person automatically inherits the house, known as the Igiogbe, where the deceased lived and died. Consequently, a testator cannot legally bequeath the Igiogbe to anyone other than his eldest surviving male child. Any attempt to do so in a will is invalid. This principle was affirmed in Agidigbi v. Agidigbi (1996).

The changing fortunes of women in court regarding inheritance rights are thanks to the refusal of catalysts like Caroline and Gladys to back down in the face of sanctioned oppression.

Today, Nigerian women have the legal right to inherit and can access legal justice with fewer obstacles. Unfortunately, for many people, this is still not enough. Awareness and understanding of the law’s position remain low, and grassroots community leaders are divided. While some see the actualisation of women’s rights to inherit as a good development, others see it as an attack on their culture, so they are hostile towards change.

Despite the progress made over the decades, many women remain victims of inheritance discrimination, including those who consider fighting expensive legal battles against their families as unnecessary. To create a fairer world for women, more awareness is necessary—the importance of the law’s position must be communicated in a language everyone understands.

More crucially, structured legislation must exist for people to easily access when they have questions, and penalties enforced for people who do not comply.

Credits

Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Illustrator/Director: Owolawi Kehinde

Researcher: Olalekan Ojumu