What If 2025 Nigerian Women Could Reply to 1970s Agony Aunt Letters?

Imagine a time when a woman's deepest fears and wildest questions could be whispered only onto the pages of a magazine. No podcasts, internet comment sections, or viral TikTok rants—just ink, paper, and the hope that a stranger's advice might save your sanity. This was the reality for literate Nigerian women who turned to Agony Aunt columns as their lifeline.

It is easy to disregard these columns as merely peddling and recycling gossip, but they were revolutionary in print. Women were suddenly confronted with a variety of questions that many in their immediate communities could not advise on. With limited precedents and even fewer relatives experienced enough to answer these pressing questions, many women placed their trust in magazine confidantes like Dolly at DRUM.

These agony aunts were the original therapists, influencers, and aunties-on-main combined. Their advice was sometimes wise, sometimes predictable—“Just pray harder, dear!"—but always reflected the times they lived in.

Become an ARCHIVI.NG member and get updates straight to your inbox

Magazines as Midnight Therapists

The first recorded advice column was written by 32-year-old John Dunton in 1691. He was a member of the Athenian Society and established a group to provide answers to questions posed by readers. A more intriguing version of this origin story is that Dunton was struggling with guilt over his adulterous affair and sought a space to receive advice without being exposed. In 1693, women began submitting inquiries, and other groups started adopting the format, which was very effective at engaging readers. An Agony Uncle emerged in 1704, but by 1740, women had become the majority of readers, leading to more 'aunts' appearing and a new vertical being created.

The Nigerian press was not as 'liberal' to begin with. Almost every early newspaper was owned by a politician or affiliated with political groups, indicating that some things haven’t changed over time. This meant that it took a while for this phenomenon to cross the Atlantic and reach our shores, and when it did, it was through established magazines that often focused on these issues.

A Decade of Reinvention

Nigeria in the 1970s was shaped by the aftermath of the Civil War and a growing economy fuelled by rising oil prices. Two coups and an election also transformed an environment that saw all women gain the right to vote. In the wake of several significant moments, various ways emerged for people to feel a sense of community as they responded to these events. For women, especially on the brink of experiencing more independence than ever in Nigerian history, this meant seeking advice outside their traditional communities. It meant picking up a magazine.

Titles like DRUM, which started as a South African magazine in 1951 and was styled as "the first black lifestyle magazine in Africa," came to the forefront. Others included Lagos Life and New Breed, both established in 1972 for an increasingly literate population who found answers to questions that many assumed were sacrosanct within these pages. Their advice combined tough love with scripture, and promoted personal values and the cultural tendencies of that era.

As eras changed, Nigerian women found new avenues to engage, seeking advice. By the 1990s, Hints of defiance emerged as advisors began questioning toxic relationships, though still couched in tradition. The 2000s digital boom saw forums like Nairaland democratise advice, blending scripture with pragmatic career tips, and then it evolved to Facebook pages in the early 2010s.

With more internet connectivity and democratised access to information, women could find advice even faster and in more mediums. Social media accounts dispensed hot takes; media personalities built empires off the traffic of dealing with human issues; and podcasts such as I Said What I Said (ISWIS) and Diary of A Naija Girl (DANG) provided more options to engage.

But what if we could bridge these eras? As women grapple with questions about how fast or stalled progress has been today, it's worth taking a big picture of what women had to deal with yesterday, and if we can find lessons in how they found encouragement then.

What if today’s feminists, CEOs, and Gen-Z shakers answered the 1970s' most urgent pleas? Let's time-travel through the ink-and-paper angst of the past and see how far we've really come.

Yesterday's Problems, Today's Solutions

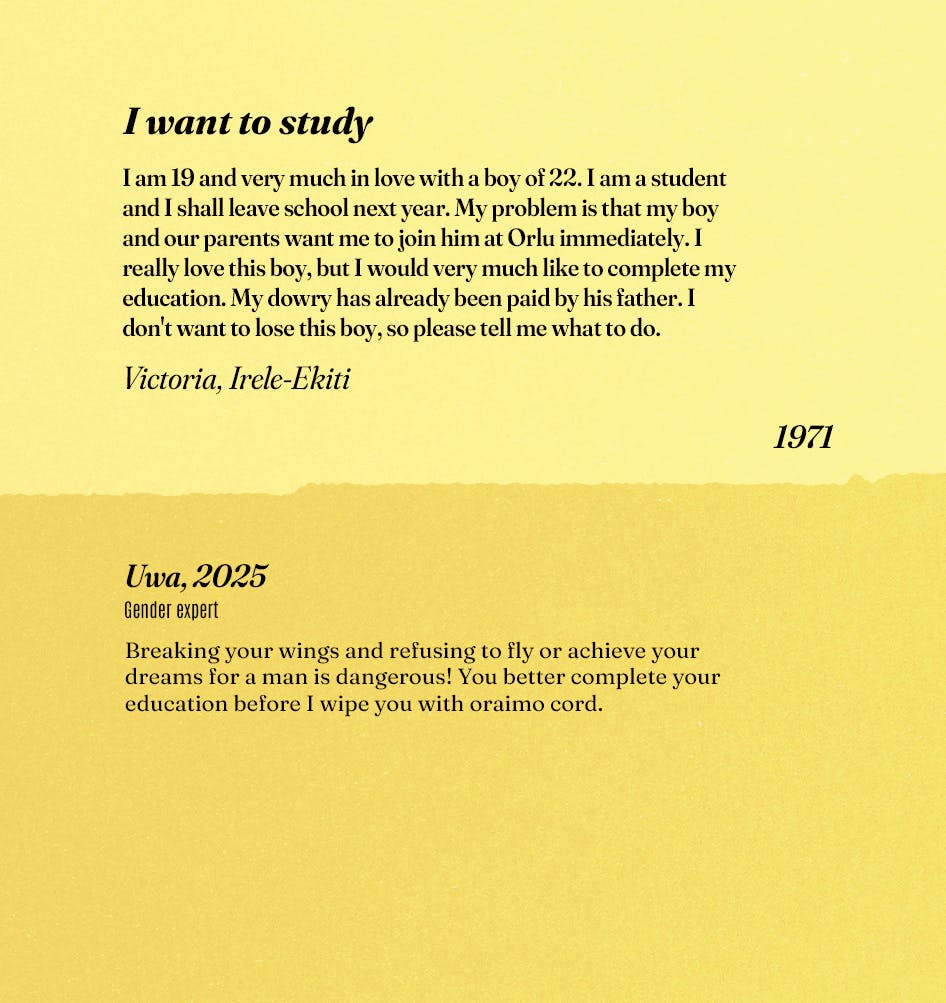

Victoria, 1971

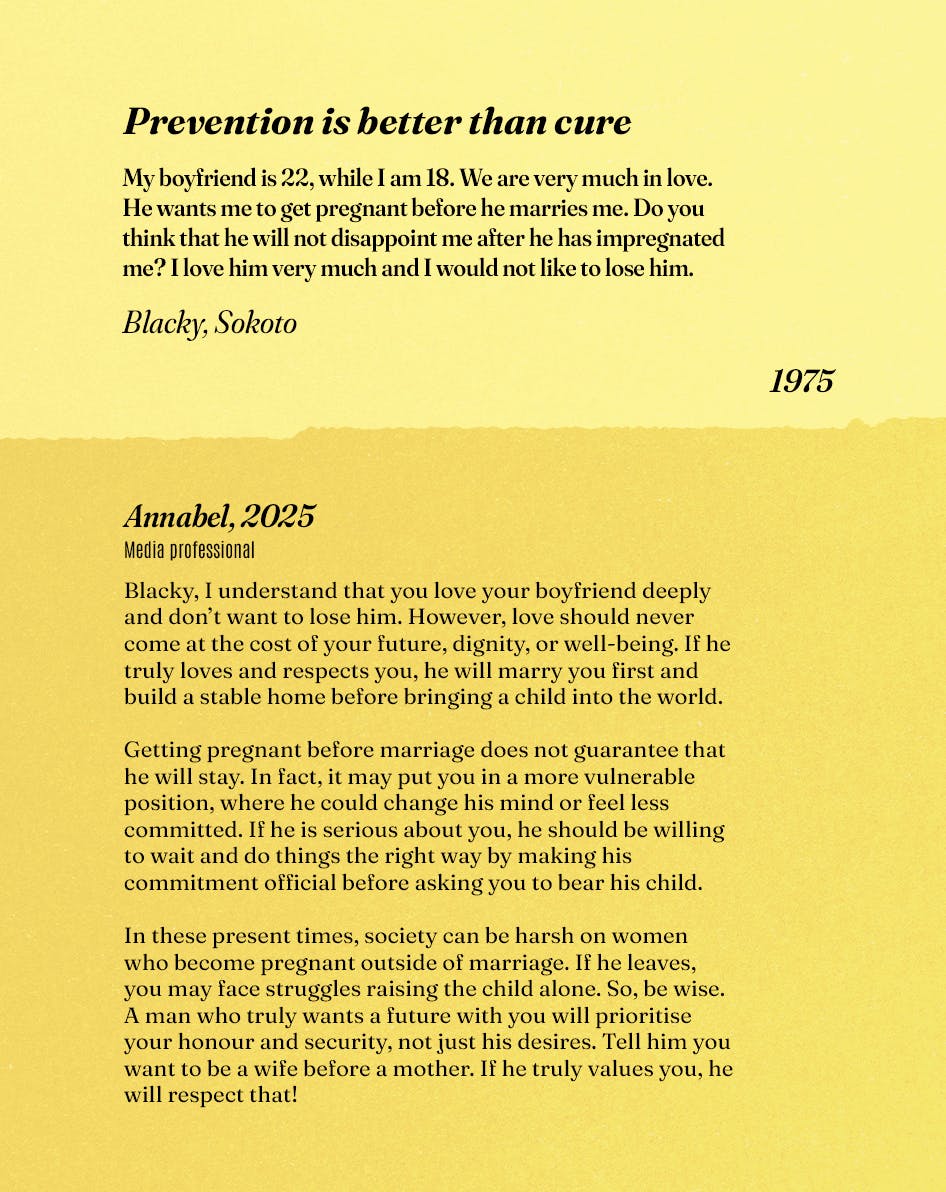

Blacky, 1975

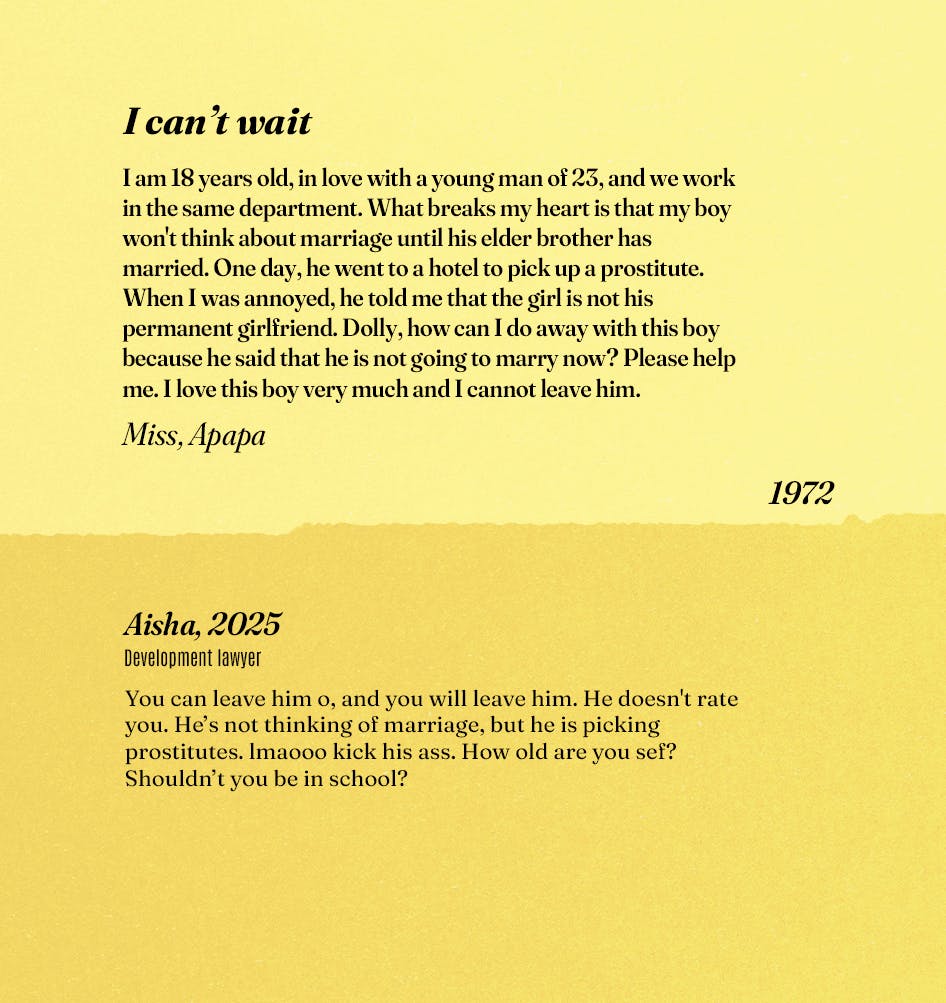

Miss, 1972

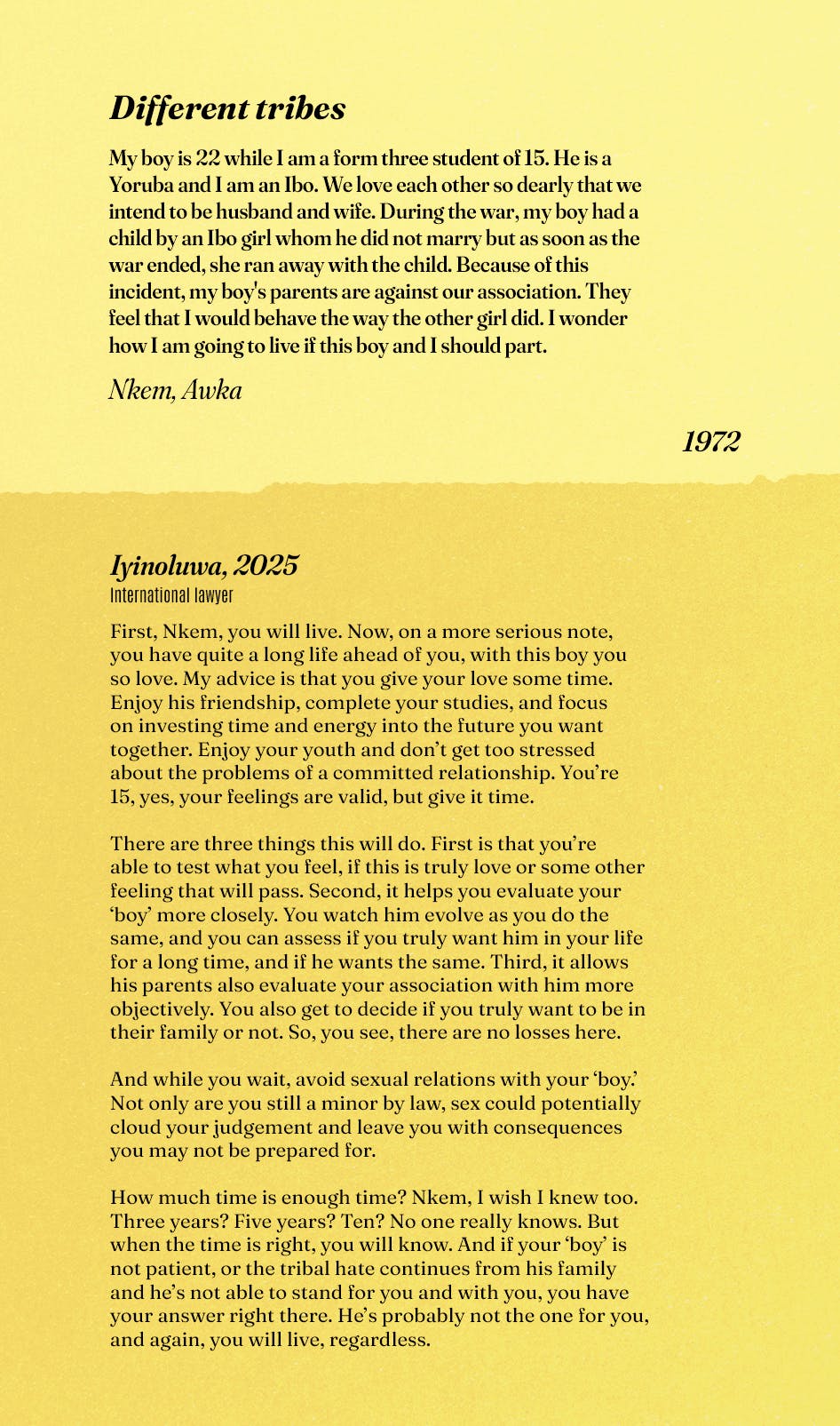

Nkem, 1972

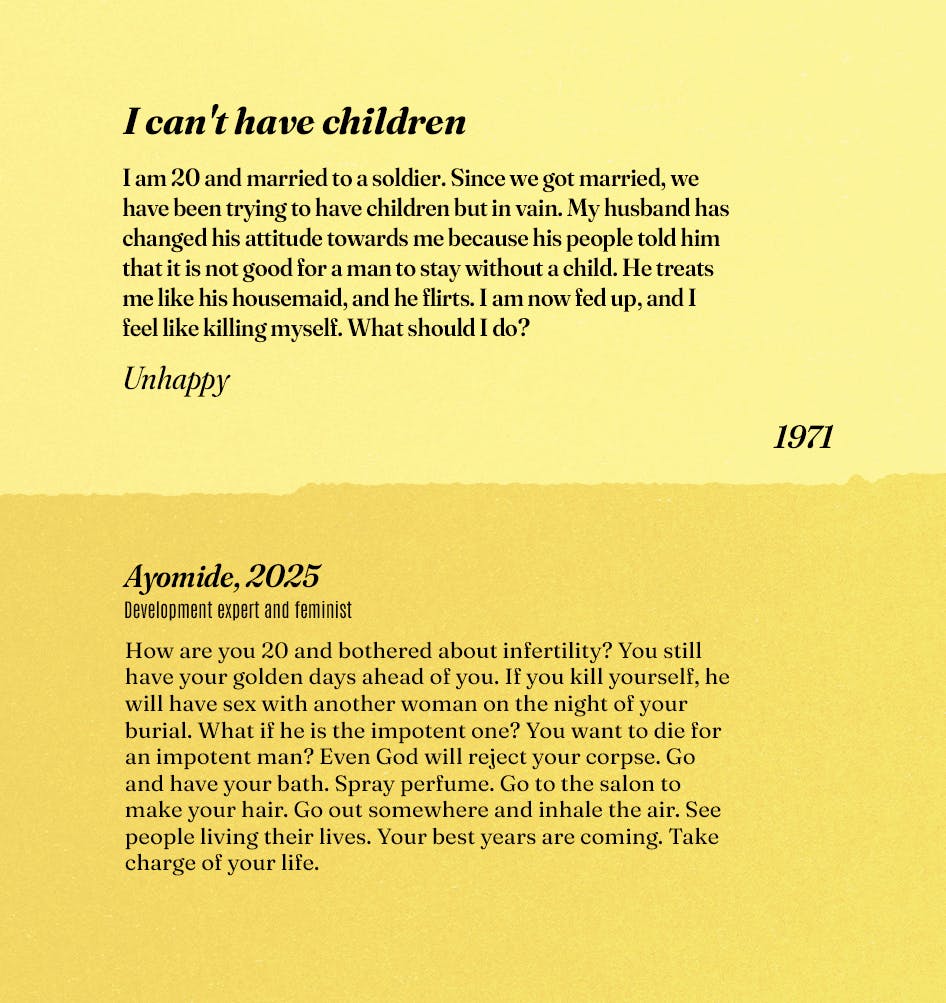

Unhappy, 1971

Old Wines, New Bottles

The letters written by Nigerian women in the 1970s read like fragments of a shared diary, each echoing similar aches. The pages were stained with tears, fears, and the quiet desperation of a generation navigating a world in flux. Their modern counterparts, armed with hashtags and enjoying greater opportunities, might cringe at the constraints of that era, but the echoes of those struggles reveal a truth: progress is not linear. Old battles resurface in new disguises, and hard-won freedoms can coexist with stubborn regressions.

In the 1970s, a woman's worth was often measured by her wifely obedience and her ability to bear children. Today's advisors reject this fatalism, urging women to walk away, seek therapy, or explore fertility options—a testament to how far we've progressed in separating womanhood from motherhood. Legal reforms, such as the Violence Against Persons Prohibition Act (VAPPA), along with a growing culture of financial independence, provide avenues to exit toxic marriages that women in the 1970s could only dream of. Virginity, once a currency for marital negotiations, is now a footnote in a broader conversation about consent and agency. The shift from "wife" to "graduate" as a societal badge of honour is undeniable.

Some struggles, however, wear the same face across decades. Tribal tensions persist in subtler forms, like families opposed to cross-cultural relationships or politicians weaponising ethnicity in the struggles for power.

The good news is there's power in the sheer volume of voices now shouting where whispers once sufficed. The woman of the 1970s wrote her letter in secret, mailed it, and waited weeks for a reply. Her descendant in 2025 live-tweets her heartbreak, crowdsourcing advice from strangers in Lagos, London, and Los Angeles. This democratisation of wisdom—flawed, chaotic, and often contradictory—is progress. It acknowledges that women's pain is not private but political, not singular but shared.

But progress for whom? Today's advisers, though passionate, often speak from urban, educated bubbles. The majority who are on the peripheries lack the same access to online discourse. While those in urban spaces can afford internet subscriptions to stream the latest podcast or browse at leisure, many still rely on guidance from older relatives and cultural or religious figures. These sources are not inherently wrong, and progress has been made, but their advice is filtered through cultural and religious traditions that are typically set in stone.

As conversations around womanhood expand, new challenges come to the fore—the queer woman concealing a partner for fear of losing family, the woman who doesn't want children for fear of transferring trauma, the older careerist worried that her "failure" to marry reduces her status and even the politician accusing a powerful figure of sexual harassment. A new age brings new voices and stories, alongside those that have long persisted and still demand attention. After all, liberation that elevates some while leaving others behind isn't liberation; it's curation.

As we reflect on women's past concerns, we must ask: What blind spots will future Nigerians find in our answers today? Progress is not a destination but a relentless, collective push—one that demands we honour the whispers of our grandmothers even as we shout our truths. After all, the Agony Aunt's greatest lesson is this: every generation's solution is just a stepping stone for the next.

Credits

Editor: Afolabi Adekaiyaoja

Copy Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Illustrator/Director: Owolawi Kehinde