Old Nollywood Revolutionised Sex, And Punished It

In the 1990s and 2000s, Nollywood brought sex into the living room.

Cheap VHS tapes flooded the market, making it easier than ever for filmmakers to spin wild stories that travelled far and fast. Kenneth Nnebue’s Living In Bondage kicked the doors open for an emerging industry, and nothing was too taboo to touch.

These VHS tapes delivered tales of hustle, family, survival and lust straight into people’s homes. Everyone was watching. Everyone was talking.

Alongside everything else, the home video boom turned young, attractive women into household names. They played the role of ambitious women who would do whatever it took to get what they wanted. They were everything Mike Okri foreshadowed in his 1989 hit song, Omoge: fast, loose, and street-wise. We saw them on TV, while surrounded by family.

In the 1992 Yoruba flick, Asewo To Re Mecca (The Sex Worker Who Went to Mecca), Sola Sobowale and Toyin Adegbola play sex workers on a redemption arc. After years of sleeping their way through Nigeria’s elite, they seek a spiritual reset. It was wild, satirical, and real.

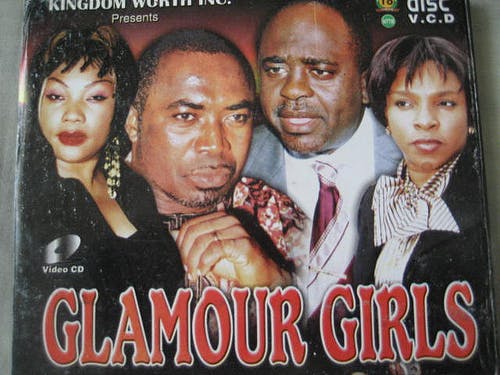

Then came the one that opened the floodgates of Nollywood sex films. Glamour Girls (1994) is the story of young women who become escorts to survive and thrive in a patriarchal society. Written by Nnebue and directed by Chika Onukwufor, the film accurately nails the underbelly of Nigerian society of the time: get rich by any means necessary. Its theme illustrates the dynamics of cold hard cash by men of means, and the young women using what they have to get what they want.

Image Credit: IMDb

The sequel was even bolder. Glamour Girls 2 mocked every moral line Nigeria thought it still had. The steamy bathtub scenes with Zack Orji and Eucharia Anunobi became the centre of public obsession. Add snakes crawling into forbidden places and a sugar baby cooking for her sugar daddy with water used to wash her private parts, and you have a full-blown scandal.

Glamour Girls 2 not only flashed a middle finger to conservative dispositions but also proclaimed the sexual revolution of the 1990s ushered by Nollywood.

What these home videos lacked in high production value and technical quality, they made up for by telling raw, unfiltered stories. By design or happenstance, Nollywood became a mirror reflecting the ills of a cut-throat society where the end justified the means. It showed the corruption of the mind, conscience, and body. What was once held sacred was now an opportunity for ill-got wealth. Whether it’s young men stealing a precious sacred artefact from their village’s shrine, or desperate men dining with the devil for riches or women walking the cold, hard Lagos roads for a quick buck, it all made sense in a world where survival was all that mattered.

Become an ARCHIVI.NG member and get updates straight to your inbox

There Was a Catch…

The chase for quick bucks had consequences in the Nollywood universe. The shrine thieves die. The occultist loses his peace of mind. And women who do sex work meet an inglorious end: HIV/AIDS or death at the hands of ritual killers. Nollywood struck gold, especially with its sexploitation films.

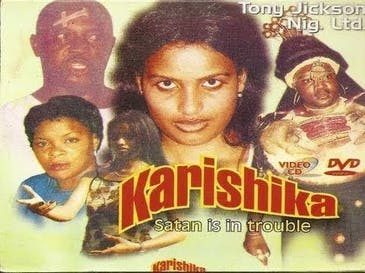

The trailer of Domitilla (1996), a blunt and grim portrayal of sex work, carried a stern warning: “Asewo no be work” (Sex work is not a dignified career). In spiritual thrillers like Karishika, Sakobi, and Samadora, sexy women came from hell, or the sea, bent on seducing men, stealing souls, and snatching husbands.

TJNL

Samadora, especially, takes the cake in the world of Nollywood sexploitation. Played by Tricia Esiegbe, a daughter of the sea world, who’s desperate for a husband, travels to Earth and sets her sights on Ken (Charles Okafor). To get rid of Samadora from taking him to the marine underworld, Ken pees on her. Years before urophilia became a mainstream fetish, Nollywood was already knee-deep in it.

Girls' Hostel (2000) pulled the curtain on campus life, depicting a world of sugar daddies, quick money, and runs. Empress Njamah plays a wide-eyed student who’s sucked into the fast lane. By the end, she crashes and burns. The flick embodied Nollywood’s winning formula: seduction, satisfaction, then swift punishment. Old Nollywood never left a loose end. Every forbidden pleasure led to punishment, by death or the crushing weight of shame.

Censors and Scapegoats

By the 2000s, the gloves were off. Nollywood tested the limits at the turn of the new millennium. More daring filmmakers released more sexually explicit films that provoked the public moral police and the National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB).

Three films in particular teased the edge of softcore porn and invited the full force of the regulator, created in 1993.

The Prostitute (2001) starring Omotola Jalade-Ekeinde, about a young girl forced into the grim world of sex work, caused a moral meltdown for its poster and sex scenes. The same year, Chico Ejiro’s Outkast, about deported sex workers who turn to crime, featured a poster of Shan George, topless, clutching her breasts like Lil Kim on the cover of her 2000 album, The Notorious K.I.M. The film’s sex scenes tipped many viewers over.

But the real trouble came with Shattered Home (2002), featuring Cossy Orjiakor as one of a pair of sisters who enter a world of vice and sex work due to parental neglect. Also starring veterans like Orji and Chinyere Wilfred, Orjiakor’s voluptuous frame and provocative barely-there outfits caused an uproar.

As the film flew off the shelves in video clubs across the country, the NFVCB reacted, claiming the producer forged its logo for approval. The board stated it never approved the controversial film for public viewing. In a P.M. News article titled “Cops Chase The Nudist,” published on March 13, 2002, it was revealed that the Nigerian police were looking for the film’s producers.

When the Curtain Falls

As these films flooded the market, the lines blurred between character and actor. In a 2024 interview, Zack Orji revealed that he was suspended by his church for appearing in sexually explicit scenes, and his marriage experienced some turbulence. For the women, the scrutiny was harsher, the backlash more personal, and the consequences longer-lasting.

The Prostitute clashed with Jalade-Ekeinde’s clean-cut image of a family woman, and an actress who mostly played sweetheart roles onscreen. She told Encomium in 2015 that she did not shoot the controversial sex scenes, but the public pressure affected her marriage.

“That was the first major fresh shaking I had. Nigeria was not ready for that, so there was a lot of controversy around that. That was the only time I really worried about my marriage."

Orjiakor became Nollywood’s poster girl for softcore porn, and suffered in the press. Her career never hit the big time, featuring in one B-rated film after another, objectified by Nollywood producers. Her acting opportunities took a bigger hit after a journalist ran a fake story in 2002 claiming she slept with dogs in a porn film. 20 years later, she recounted the experience in an interview with PUNCH.

“The pictures that went viral were taken on the set of a movie I was acting in at the time. It was a make-believe thing. Besides, there were a lot of people around (on the set), including the director and his wife. I don’t know if he (the journalist) was just trying to promote the movie. He just put the story on the cover of the newspaper.”

Orjiakor was mocked, falsely shamed as a carrier of HIV/AIDS, and blacklisted. Churches used her to make a point in sermons. Journalists dragged her name through the mud. The industry that made her turned its back when things got hot.

In March 2002, P.M. News ran the headline, “Nude Actresses Under Attack.” Written by Ayodele Lawal and Niyi Tabiti, the article featured comments from Nollywood filmmakers who slammed the actresses who had jumped on the nude trend.

“My wife can never pose nude for any amount whatsoever. She comes from a good Christian background, and all her scripts come to me first. So, if it is a role I find not worthy, she won’t act because I have to guide her like my daughter,” legendary Reggae act, Orits Wiliki, said.

But the late actor, J.T. Tom West, pointed out what he believed to be double standards. He questioned why Nigerians fussed over local films with sex scenes and nudity when they watched similar things in Hollywood projects.

“How come we are now condemning it when our acts are doing something similar?”

He had a point. Hollywood films like Basic Instinct, starring Sharon Stone, were widely popular in the country and did not face the same intense moral outrage. No one was regulating them.

And that’s the story: a generation of films that gave Nigerian women agency and then snatched it away. That let them want, seduce, and win; only to slap them with death, disgrace, or disease. It played out in the films just as well as it played out in real life.

Old Nollywood’s sexploitation era wasn’t just scandalous, it was a battleground. And for a while, the baddies were winning, but they rarely made it to the end credits in one piece.

Footnote

This story is an excerpt from Ayomide Tayo's forthcoming book: 'From Ojuelegba to the 02: The Story of the Afrobeats Generation'

Credits

Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Illustrator/Director: Owolawi Kehinde