The 50-year-old Lagos Art Gallery That Love Built

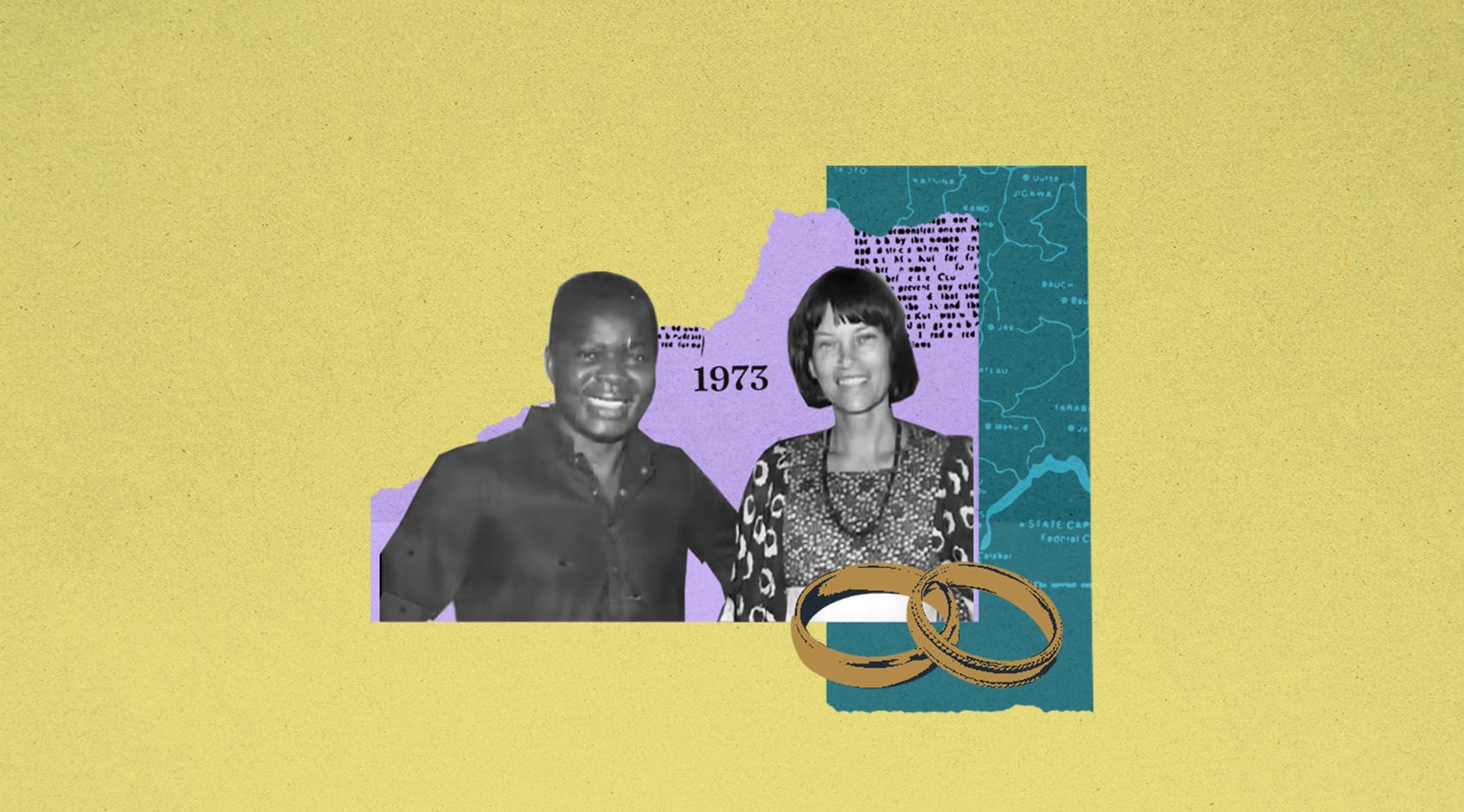

In the early 1970s, a Swedish textile artist and a Nigerian visual artist crossed paths in the United States. What began as a meeting of creative minds soon evolved into something deeper.

The textile artist, Aino Ternstedt, was born in 1939 and received her first degree from the School of Arts and Crafts in Sweden. Afterwards, she opened a studio in Stockholm and practised for nine years. In 1971, she was awarded an American-Scandinavian Scholarship to study Fine Arts at the California College of Arts and Crafts. It was during her time in the US that she met the man who would eventually become her husband.

Gabriel Olusegun Oni-Okpaku, roughly a year older, spent his early years in Onitsha but moved back to Lagos for his secondary school education and then to the United Kingdom for his bachelor’s and master's degrees before returning to Nigeria. Still unsatisfied, he set off to Rome, Italy, to study the arts. He then began lecturing at Stanford University, California, where he met Aino.

When they moved to Nigeria in 1973, the Ministry of Education recruited Gabriel to teach arts in King’s College, Lagos, while Aino worked as an interior designer at Godwin and Hopwood Architectural Firm, also in Lagos.

get updates straight to your inbox

Gabriel and Aino were lovers of good music. They had various Hi-Fi systems in their Apapa home and often had friends over to listen to music and sample the equipment. These sessions usually led to Hi-Fi equipment sales, so it only made sense that they built this love for community and music into something bigger.

In 1975, Gabriel left his teaching job at King’s College to bring the idea of Quintessence to life with his wife, starting a store in the heart of Falomo, Ikoyi. Describing themselves as audio perfectionists, they sold Hi-Fi equipment, intending to bring the best the world had to offer to the Nigerian market. They also sold luxury furniture pieces such as the renowned Eames lounging chair and products by the Swiss brand, de Sede.

At the time the store was established, Nigeria bristled with hope and promise. “Nigeria had just come out of the civil war, there was money from the oil boom, there was a great potential to grow, and they both believed they could contribute to that,” Vincent Aruofor, Gabriel’s nephew and former Quintessence manager, tells me over the phone, pausing in between sentences to relive the nostalgia.

However, tragedy struck in 1977, merely two years after operations began. Gabriel died.

Grief

Gabriel Oni-Okpaku was an established painter who once showcased his work at the Italian embassy. His other interests included horse riding, squash, and tennis. He also loved to listen to classical music and, according to Vincent, owned one of the greatest classical music collections.

When Gabriel died during a horse riding accident, Aino lost her partner, her co-founder, and the stabilising presence in their shared dream. For a time, it was not clear what would become of Quintessence, or Aino herself.

She had always been hardworking, Vincent says, but when the love of her life died, a shift happened. Her drive doubled as though grief had handed her a new kind of resolve, one fuelled by duty as much as love.

The decision to forge ahead was sealed in a moment she shared with Vincent, who was merely fifteen at the time. When Aino asked him, “What do I do?” Vincent said to her, “I think he would have wanted you to continue what you both started.”

To cope with her loss, Aino dedicated herself to work, to Quintessence. Then came the ban on importation.

Grit

In 1978, Nigeria's military government required all establishments selling imported items to acquire an import license through a hectic process. Businesses like Quintessence, built on access to global design and equipment, suddenly found themselves backed into a corner.

“We had to go to the Old Secretariat in Ikoyi for an import license because Lagos was the seat of government,” recalls Comfort Bruce, who worked at the store as a manager between 1976 and 2000.

“Getting the import license was cumbersome, so there was a need to begin to restructure the business.”

The business started looking inwards, for locally made goods, sourcing adire fabric, cane furniture, ceramic wares and art from different parts of Nigeria. What started as a survival move soon became a strategy that transformed Quintessence from a showroom for imported taste into a gallery of Nigerian creativity.

“The encouragement we received made us start showcasing Nigerian arts in exhibitions in Italy, England, and South Africa. Aino was all over the place to see to its success,” Comfort says.

Aino probably didn’t know it then, but Quintessence’s transition from being a Hi-Fi and luxury furniture store to one that sold and exhibited locally made goods would make the establishment something far more culturally significant: an art gallery and cultural space that has quietly but powerfully resisted cultural erasure while spotlighting African artists across generations.

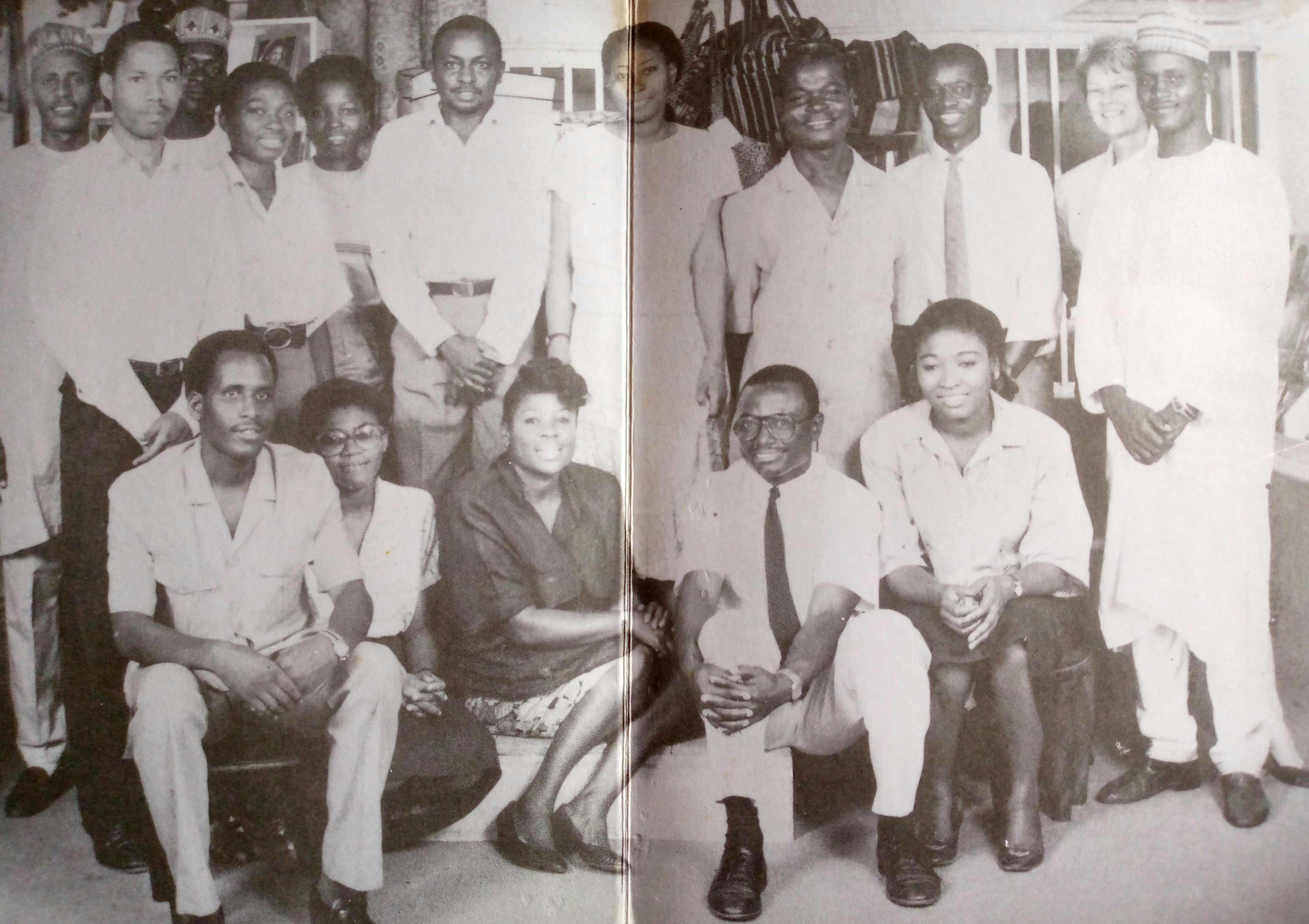

Aino and Vincent at the centre of a Quintessence group photo taken in the early 1980s

Legacy

Under Aino’s curatorial eye, Quintessence has championed African art across generations and beyond Nigeria’s borders. The gallery’s exhibitions have travelled to countries including France, Ghana, Germany, Senegal, and Aino’s native Sweden, helping local artists on international stages.

The gallery has held on to that vision of nurturing talent, giving emerging and established artists a space to thrive, and inspiring change. Quintessence has featured the works of esteemed artists like Ben Enwonwu, Bruce Onabrakpeya, Kunle Filani, Kolade Osinowo, Lamidi Fakeye, Reuben Ugbine, Sam Ovraiti, Umar Aliyu, and Zinno Orara. It has also brought upcoming artists, such as students from ABU Zaria, Auchi Polytechnic, and Yaba College of Technology, to the limelight through solo and group exhibitions.

“Ordinarily, an art gallery is not a place where tales are told. But when the gallery is filled with vintage creations of acclaimed masters, drawn from cultures as far apart as Africa and Europe, with media of expression from sculpture to furniture, then a story is inevitable,” Niji Akanni wrote in a 1990 article published by The African Guardian, describing a ten-day exhibition by Quintessence.

Some of the biggest names in the Nigerian art scene trace their early roots to Quintessence. Now thriving and well-established, galleries like Nike Art Gallery, Colours of Africa, and Out of Africa began as art suppliers to the store.

Vincent believes the gallery’s work is even more important in a place like Nigeria, where art is not done for art’s sake, but is instead interwoven into the people’s culture, deeply connected to their spirituality, and is an expression of who they are.

In the mid-1980s, a nine-year-old Bolaji Alonge walked into Quintessence with his aunt to buy a wooden puzzle map of Nigeria. Forty years later, in 2019, he returned to the store, this time as an artist, photographer and journalist, to host a black-and-white photo exhibition. When Aino first invited him to exhibit at Quintessence, it was a “wonderful homecoming.” His branded merchandise, Eyes of a Lagos Boy/Girl T-shirts, has been on sale in the gallery for years, and he often visits with his wife and friends to browse for books, carvings, gift items and mementoes.

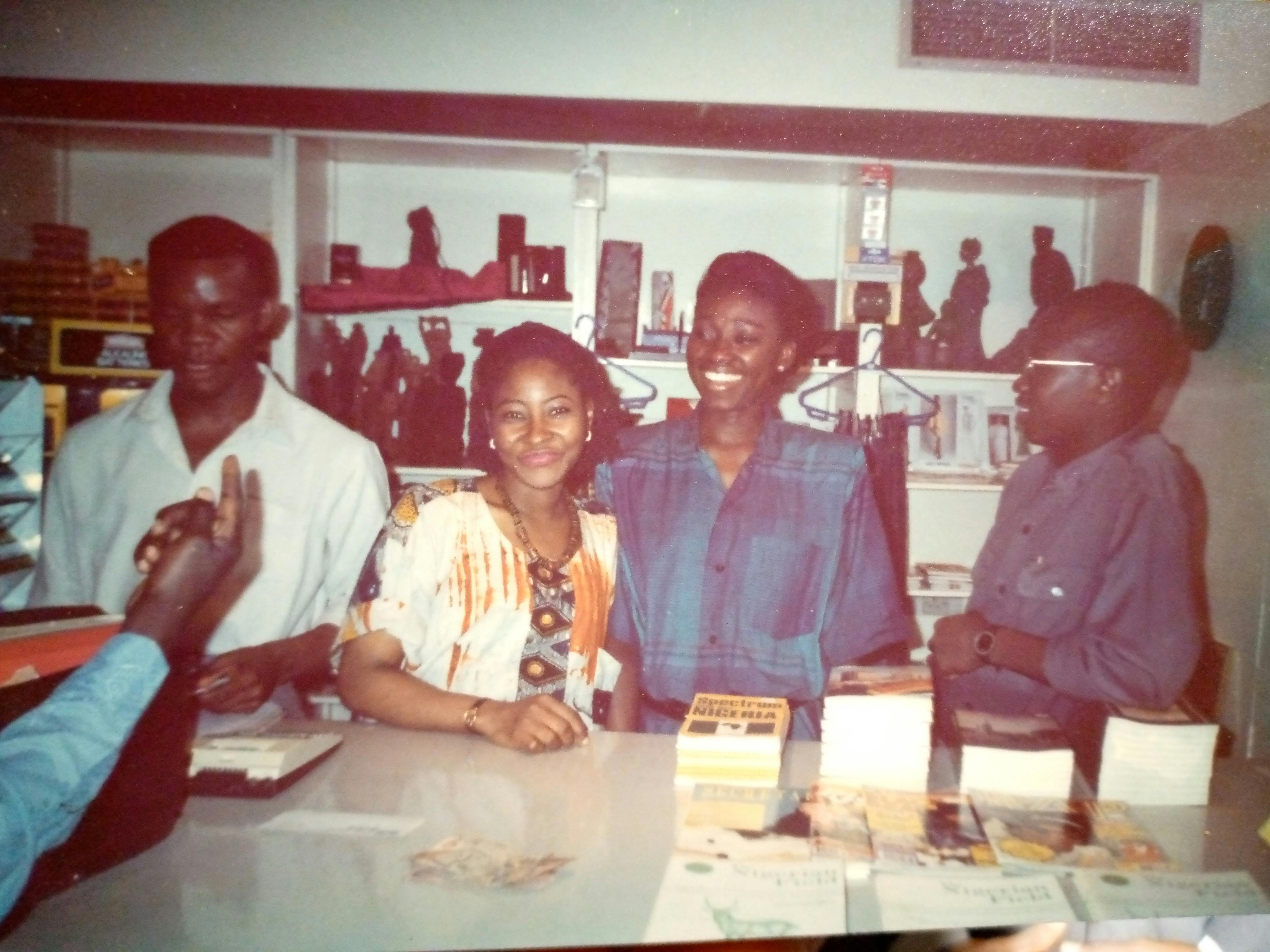

Front desk of Quintessence in the 1980s and 1990s

Jude Oni-Okpaku, son of the founders and also the current CEO of the establishment, tells me that, “Aino’s vision for Quintessence was of an inclusive space where both emerging and established voices could converge to celebrate and challenge cultural narratives.”

That vision is still being translated into reality. Beyond being a living archive of over a thousand art pieces, the gallery opens its doors to creatives and art lovers to build lasting connections and foster inspiring conversations through book readings, reviews, poetry and music events.

While the years rolled on with grief lingering in corners, Aino remained fierce, getting up every day to devote her time to the gallery. Quintessence grew in leaps and bounds, and so did the staff members, some of whom worked at the gallery for decades.

A lineup of Quintessence staff who worked at the gallery in the 1980s and 1990s

For Moses Ohiomokhare, an art consultant and curator who started working there in 1983 as a trainee manager, Aino’s fierceness seemed like something to fear initially because she was a stern, “no-nonsense” person. But with time, they gained an understanding of each other and became friends.

For my mother, Biodun-Oloko Ogunlana, an entrepreneur who worked at Quintessence for twenty-four years, initially as a sales assistant and then resigning as a manager in 2007, Iya—as Aino was fondly called—was a compassionate woman who always encouraged her staff and others to do more for themselves.

“She was a blessing to anyone who crossed her path.”

Hakeem Ariori started there as a doorboy in 1983 and left ten years later as a purchasing officer. He describes Iya as someone who couldn’t withstand laziness, and as a go-getter who sometimes wanted people to see things “through her eyes.”

Final Honours

Aino seemed like someone who never fell ill. She was strong. Always active, always working. According to Comfort, she was the first to arrive at the store and the last to leave. So when one day, she called Vincent to tell him she was feeling ill, it was perplexing for him. He had known her for about 50 years, and he never remembered her even coming down with malaria.

On December 26, 2019, Aino passed away in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Jude remembers Aino as someone who could turn even ordinary moments into celebrations of beauty [Södertälje Art Gallery]

Jude says his mother’s belief that art is an essential tool for connection, healing, and change continues to guide his leadership and the strategic direction of Quintessence.

Aino may be gone, but the love she built with Gabriel lives on in every brushstroke and sculpture, in the music of the gallery’s quiet rooms, and in the artists who found home within its walls.

Credits

Editor: Kunle Adebajo

Copy Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Illustrator: Adeoluwa Henshaw

/The African Guardian May 14_1990_Pg 44.jpeg)