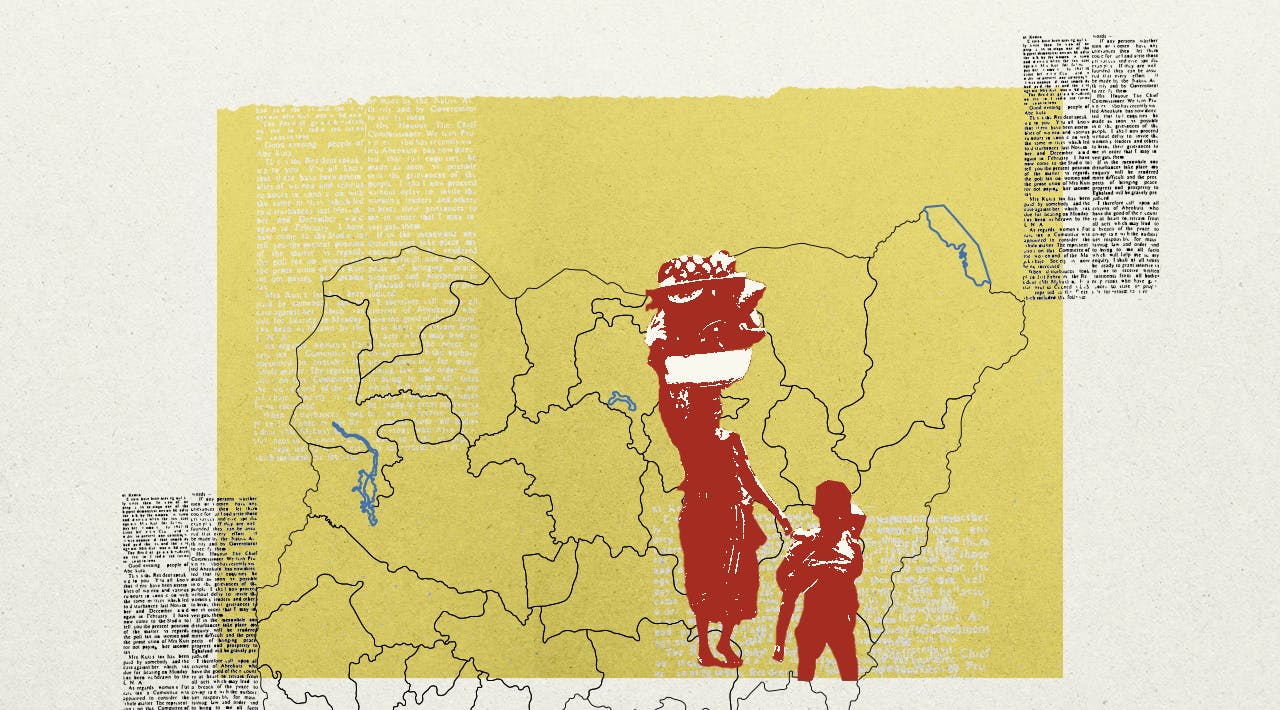

How Radio Biafra Carried a Nation Through a War

The Nigerian Civil War did not begin with gunfire for Nneka Benjamin. In her memory, it began with a radio announcement.

She was only 12 years old in 1967, in her father’s sitting room, when Umuhaia’s tense air was broken by his radio’s static. Then she heard the voice that would shape her new reality. It was not music or a sermon. It was a declaration of a new republic and a promise of resistance.

“I, Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, …do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region known as and called Eastern Nigeria together with her continental shelf and territorial waters shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state of the name and title of The Republic of Biafra.“

It was May 30 as Nneka listened to Ojukwu’s words, cutting Biafra from the rest of Nigeria. That radio had always been her father’s companion; his source of daily news. But that day, it announced a revolution, and a new country had been born.

The Nigeria-Biafra War was preceded by a series of crises. In January 1966, a coup overthrew the civilian government of Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa. This was Nigeria’s first military coup and saw both Northern and Western Region leaders killed. It resulted in the assassination of Tafawa Balewa; the Sardauna of Sokoto, Ahmadu Bello; Premier of the Western Region, Samuel Ladoke Akintola; and Finance Minister, Festus Okotie-Eboh, in an attempt to rid Nigeria of its “corrupt” ruling class. The fact that prominent Igbo leaders were not touched led many to call it an “Igbo coup.”

A counter-coup followed in July, orchestrated mostly by Northern soldiers as a reprisal for January. The counter-coup led to the death of the military governor of Western Nigeria, Francis Adekunle Fajuyi, and the Head of State, Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi.

In 1966, 30,000 Igbos were massacred in a pogrom in Northern Nigeria. Across the region, Igbos were harassed, some killed for how they pronounced words, and others for the names on their identity cards. Survivors like Nneka’s family abandoned everything they knew in Lagos and fled. Eastern Nigeria first became a refuge and eventually a republic.

Twenty-four hours after Ojukwu’s announcement, the Northern-led Federal Military Government under Yakubu Gowon declared the secession treasonable and vowed to crush it.

Nneka did not see the war coming. To her, the secession on May 30 felt like a promise of safety after months of ethnic violence. But five weeks after Ojukwu's declaration, on July 6, 1967, the shooting began. In the uncertainty that followed, the radio became the family’s guide, and her father, its guardian.

“It was our father who had access to the radio. When he gets the information, he tells us when we need to start running before the enemies attack the next day. They could attack any time. No one could sleep with their two eyes closed.“

Become an ARCHIVI.NG member and get updates straight to your inbox

The Voice of a New Nation

Ojukwu’s breakaway nation controlled two broadcasting networks: the Nigeria Broadcasting Corporation (NBC), with its headquarters in Enugu, Biafra’s capital, which operated on multiple frequencies with substantial reach, and the Eastern Nigeria Broadcasting Service (ENBS), which started operating in 1960, as an associate company of Overseas Rediffusion Ltd in conjunction with the Eastern Nigerian Government. Ojukwu’s government had strategically acquired this station before the war began.

With four 10-kilowatt transmitters and three smaller units concentrated in the East, Biafra commanded greater broadcasting power than Nigeria’s remaining territories with just 73½ kilowatts split between Lagos, Ibadan, and Kaduna. In a nation where newspapers rarely reached remote towns and TV ownership was scarce, this gave Biafra something priceless: a voice. The NBC and ENBS were merged to form Radio Biafra. It aired official announcements, battle updates, and ideological messaging. But more than that, it gave people something to hold on to and reminded them they were not alone.

The Biafran leadership established a well-organised Directorate of Propaganda, enlisting the best literary talents and thinkers. Dr Ifegwu Eke managed the Biafran Ministry of Information while the famous novelist Chinua Achebe, who worked for the NBC as the controller of the Eastern Region side of the broadcasting service from 1954 before the war, headed the National Guidance Committee, and Professor Emmanuel Obiechina, who at the time held a PhD from Cambridge University, served as its secretary. Creatives like Pete Edochie and his wife, Josephine, also worked for the radio after joining the Eastern NBC in February 1967. The Directorate had a simple plan: use local radio to keep Biafran spirits up.

One of the constant announcements Nneka remembered was: “Onye ndi iro gba gburugburu ne che ndu ya nje. Nde Biafra unu ararunura (He whose enemies surround always guards his life, The people of Biafra, stay alert).”

A Signal That Would Not Die

Radio Biafra became more than news. It played songs of struggle that still live in survivors’ memories. Nneka remembered one. “Papa no dey mama no dey. Friend no dey, brother no dey. I no get brother, I no get sister, trouble come, na me go carry am.” As the Biafran government moved from Enugu to Umuahia and Owerri, Radio Biafra became the voice that held communities together.

Kodiliniye Obiagwu, now a journalist, was a child during the Biafran War. His father, a former soldier, had left the Nigerian army to join the Biafran cause in 1967. “The broadcasts on Radio Biafra were so important because they gave you a boost and kept you going,” Obiagwu recalled. “There were speeches by Ojukwu. The broadcasts always ended with encouragement to keep watch. They would say, ‘Biafrans, you cannot afford to sleep.’”

As the war continued, information became currency. S.K. Okpi, a student at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, watched as communities formed around shared listening. A local palm wine tapper would give him and his friends free palm wine in exchange for sharing the latest news from the broadcasts. In this way, Radio Biafra created a community united by the shared act of listening and surviving together.

More Than Propaganda

Despite the chaos, people like Nneka remember the radio not as a propaganda machine, but as their lifeline. “The radio station told us about the war,” she remembered. “The news was mostly about conquered villages, where the soldiers were approaching and how to stay vigilant of the enemies.“

As the war dragged on, Biafra lost cities to the advancing Nigerian troops. First Enugu, then Umuahia. Each time Nigerian forces advanced, Radio Biafra moved. It became a ghost signal that could not be silenced. Operators abandoned buildings and started broadcasting from forest hideouts. Nigeria tried to jam them, but the station always returned.

Nneka’s family once fled to the bush, where the wrong sound at the wrong time could mean death. Still, they kept the radio on. Even with bombs falling and food shortages spiralling into a hunger crisis, the station remained their connection to hope.

British Journalist John de St Jorre, in his book The Brothers’ War, called the civil war a “transistor war” fought as much by small radios. While Nigerian troops had more sophisticated weapons, Biafra fought the war partly on the airwaves. People repurposed batteries and built transmitters from scraps. In some villages, children were sent to fetch copper wire and battery acid just to keep one radio alive. When batteries became impossible to find due to the economic blockade by Nigeria, Biafrans soaked dead batteries in salt water for hours, then dried them in the sun to bring them back to life.

The station's hiding place at Obodo-Ukwu became a classic wartime deception. Major General Philip Effiong, who took over when Ojukwu fled to Ivory Coast in January 1970, called it a “mock-up station.” Even Olusegun Obasanjo, then a military officer who witnessed Biafra’s surrender, admired their cleverness.

“The station was well camouflaged from both ground and air by trees and fresh palm fronds which were changed regularly. It was a perfect job.”

The Last Broadcast

Thirty months after the war began, Major General Effiong stood before the press to announce Biafra's formal surrender. He accepted Nigerian authority, pledged loyalty to the Federal Government, and announced that the Republic of Biafra had ceased to exist.

When the war ended, survivors like Nneka had to rebuild from nothing. ”We started telling people about the suffering of the war, especially how children were affected by kwashiorkor,” she said. “Everyone started life again from scratch.”

Fifty-five years after Radio Biafra fell silent, Nneka still carries the memory of the frequencies that filled the silence of war, warned of danger, and offered comfort when the world around her was crumbling.

The station faded. The war ended. But the voices that sustained a people through their darkest hours continue to linger in the memories of those who survived on hope and sound.

Credits

Editor: Temitayo Akinyemi

Copy Editor: Samson Toromade

Art Illustrator/Director: Owolawi Kehinde