The Maitatsine Uprising That Almost Broke Nigeria

In the years leading up to Nigeria's independence, Muhammadu Marwa, a Cameroonian Islamic preacher popularly known as Maitatsine, meaning "one who curses," settled in Kano.

His nickname derived from his frequent curse, "Wanda bai yarda ba Allah ta tsine mishi," which translates to "May Allah curse whoever disagrees," and his teachings went against the usual beliefs of the time.

Maitatsine declared himself a prophet, rejected mainstream Islamic doctrines, and incorporated unconventional rituals and practices. He also claimed prophetic status, a direct challenge to orthodox Islam, which recognises Muhammad as the final prophet.

Despite deportation from Nigeria in 1962, he returned to Kano, and his radical doctrines attracted marginalised youths, rural migrants, and unemployed urban poor, forming a cult-like following.

By the late 1970s, Maitatsine had established an autonomous enclave in Yan Awaki, Kano, where his followers lived in a self-sustaining community. His influence grew as he received financial support from wealthy sympathisers and enforced strict adherence to his doctrines. His movement’s appeal lay in its promise of spiritual purity and resistance against perceived corruption in both religious and political institutions.

Maitatsine rejected Western materialism, forbidding his followers from using watches, bicycles, cars, or attending secular schools. He also denounced mainstream Islamic practices, declaring that reading any book besides the Qur’an was a pagan practice.

Become an ARCHIVI.NG member and get updates straight to your inbox

Maitatsine’s reign of terror

On December 18, 1980, police officers moved to arrest members of Maitatsine’s sect for unlawful assembly and possession of weapons, but they fought back fiercely. They used knives, clubs, and petrol bombs, and attacked officers and nearby government buildings.

The clash drew thousands of sect members from surrounding slums, overwhelming police. By nightfall, militants had torched mosques, markets, and homes, spreading chaos. Unable to contain the violence, authorities deployed the Nigerian Army to crush the rebellion.

The uprising was fuelled by long-standing grievances, including economic marginalisation, distrust of authorities, and Maitatsine’s anti-establishment rhetoric. The Kano uprising revealed the state’s unpreparedness.

Official reports claimed more than 4,000 people died during the crisis. Maitatsine was one of the dead.

The floodgates of violence

In Maitatsine’s absence, it took only two years for his sect to be in the news again, this time in Maiduguri, Borno State. The violence erupted when security forces attempted to arrest his followers at their enclave near the Monday Market.

Over 3,000 deaths were reported, including security personnel and civilians caught in the crossfire. Sect members used bows, poisoned arrows and charms, believing they were bulletproof. Once again, the Army was deployed to end the crisis. But that second event made something clear: Maitatsine’s sect rebuilt networks despite the 1980 crackdown.

The Kaduna outbreak occurred weeks after the Maiduguri violence, sparked by a police raid on a Maitatsine hideout in Tudun Wada. The sect deployed child soldiers as human shields—a first in the conflict. After a 72-hour siege, security forces ended the violence with aerial bombardment, resulting in an estimated 1,500 deaths.

But the bloodiest uprising after Maitatsine’s death happened in Yola, Adamawa State, in February 1984. Under the leadership of Musa Makaniki, a surviving lieutenant from the 1980 Kano violence, the sect seized Yola Central Mosque, using it as a fortified stronghold for five days. The militants staged a prolonged urban siege, prompting the military to deploy aerial bombardment after a 72-hour standoff. Official reports cited 2,100 deaths, but independent estimates reached 3,500. Makaniki infamously escaped while disguised in a woman’s burqa, evading capture for decades after retreating to Cameroon.

It was the Gombe crisis of April 1985 that marked the last major Maitatsine uprising in Nigeria, lasting eleven days, the longest of all sect-related conflicts. The militants infiltrated local markets disguised as traders before launching coordinated attacks. The violence resulted in over 1,800 deaths, including 47 police officers.

Maitatsine’s ghost

Even though the Gombe crisis effectively ended organised Maitatsine violence, remnants persisted in smaller cells. In May 1991, Bauchi State witnessed a devastating religious violence triggered by a marketplace dispute at a local abattoir. Over four days, frenzied mobs—many allegedly linked to Maitatsine remnants—burned churches, homes, and businesses. Estimates ranged from 80 to 500 dead, with mass burials conducted via trucks. Residents fled to military barracks, paralysing the state capital.

A similar outbreak occurred in Funtua, Katsina State, in January 1993, sparked by a quarrel between two almajirais, one of whom was under the care of a Maitatsine mallam. The clash escalated rapidly, exposing the sect’s lingering influence despite government crackdowns. The incident underscored the group’s ability to evade surveillance and recruit vulnerable youths, particularly from the almajiri system. Experts urged the government to address poverty, juvenile delinquency, and educational gaps to curb recruitment.

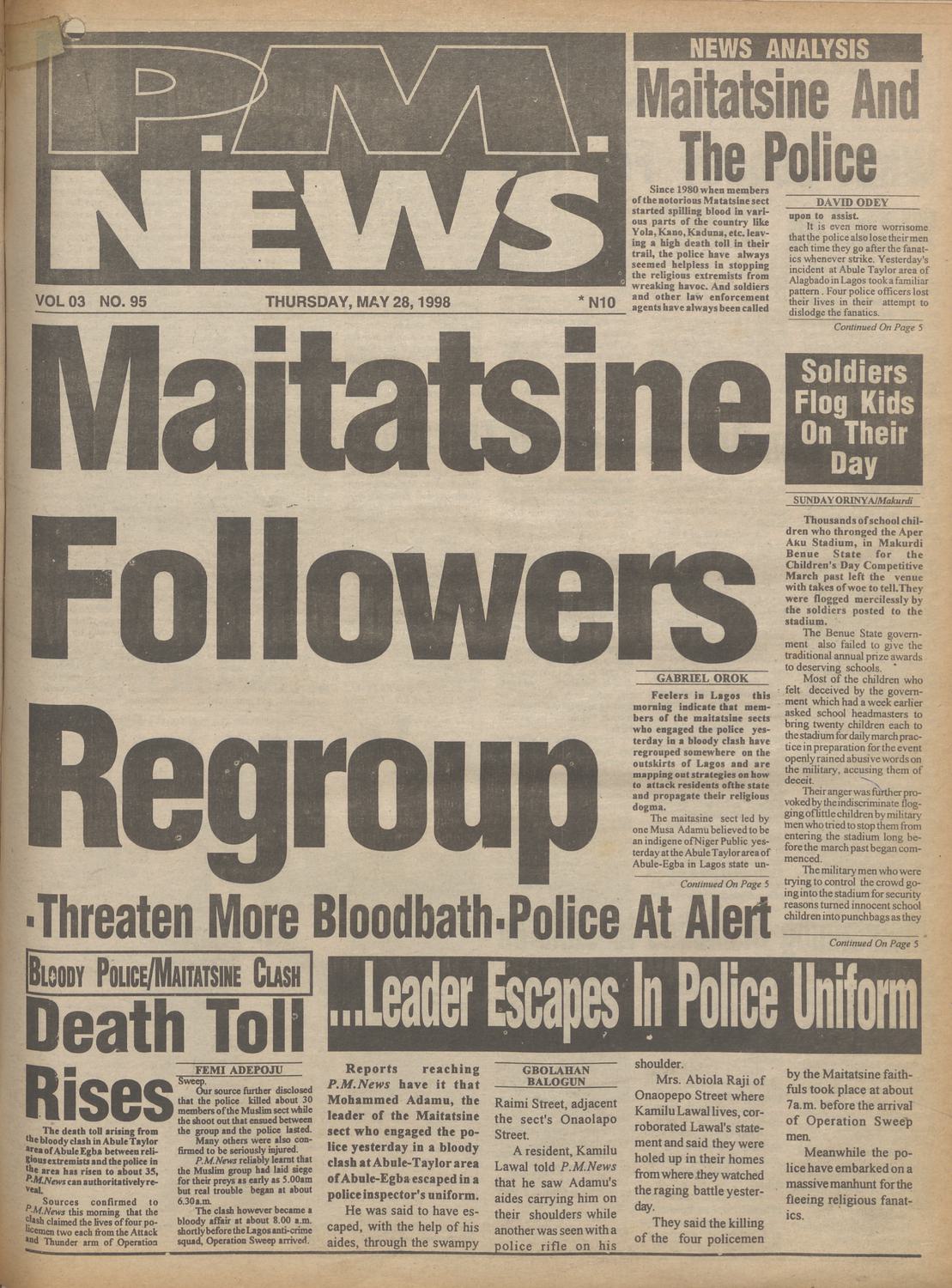

By May 1998, the sect surfaced in the Abule Egba district in Lagos, where police engaged militants in a deadly shootout. The confrontation left 35 dead, including four police officers, while the leader, Mohammed Adamu, escaped while disguised as a police inspector.

This incident confirmed the sect’s penetration into Southern Nigeria, beyond its Northern strongholds. Despite decimation in the 1980s, Maitatsine’s ideology endured for decades, adapting to new urban contexts.

A legacy of violence

The Maitatsine uprisings, often mischaracterised as purely religious disturbances, were deeply rooted in the sociopolitical and economic conditions of Northern Nigeria in the late 20th century. Poverty, illiteracy, youth disempowerment, religious manipulation, and government neglect were interconnected factors that fuelled the unrest.

The ongoing Boko Haram insurgency shares a striking ideological resemblance with the Maitatsine uprisings, reflecting a recurring pattern of religious extremism and anti-state violence in Northern Nigeria. Both movements emerged from deep-seated disillusionment with political and religious establishments, advocating radical interpretations of Islam and employing violence to challenge the status quo.

Like Maitatsine, Boko Haram’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf, was also killed during the group’s first major wave of violence in 2009.

Maitatsine condemned conventional Islamic clerics, accusing them of corruption and deviation from "true" Islam. Similarly, Boko Haram opposes Nigeria’s secular government and mainstream Muslim leaders, viewing them as complicit in Western influence. Their ideologies stem from a shared resentment towards the elite, perceived as failing the Muslim populace.

In both cases, the Nigerian government initially underestimated the threat, allowing the movements to grow in the fringes before escalating in influence. Despite the state’s suppression of the Maitatsine movement, the country was unprepared for the emergence of a similar insurgency decades later.

Rather than institutionalising early warning systems and conflict prevention strategies based on historical precedents, state responses remained reactive rather than proactive.

This failure to learn from history suggests a troubling disconnect between past events and present policy planning that should prioritise inclusive governance, equitable development, and ideological engagement.

Learning from history

In retrospect, the Maitatsine uprisings of the 1980s exposed the vulnerabilities of the Nigerian state in managing urban discontent, religious pluralism, and economic inequality.

Maitatsine’s radical preaching resonated with a disenfranchised population that felt alienated by both the secular government and orthodox religious elite. The state’s response, characterised by militarised suppression rather than holistic engagement, may have quelled the immediate threat but failed to dismantle the underlying conditions that fostered extremism.

Moreover, the Maitatsine movement exposed the complex interplay between religion, politics, and socioeconomic marginalisation in Nigeria’s urban centres. It challenged assumptions about the nature of Islamic practice in the region and laid bare the consequences of ignoring grassroots grievances. The persistence of similar patterns of radicalisation in subsequent decades, notably in the emergence of Boko Haram, underscores the historical continuity of religiously motivated dissent fuelled by systemic neglect.

Therefore, any meaningful engagement with the legacy of Maitatsine must go beyond recounting its violence; it must confront the enduring realities of poverty, political exclusion, and the manipulation of religious sentiment. Only through inclusive governance, equitable economic development, and interfaith dialogue can Nigeria hope to break the cycle of extremism and build a more stable and cohesive society.

The Maitatsine phenomenon stands as a stark reminder of what unfolds when social fractures are left to fester and when ideological movements are allowed to evolve unchecked within spaces of institutional weakness.

Credits

Editor: Samson Toromade

Cover Design: Owolawi Kehinde

/African Concord February 8_1993_Pg 01.jpeg)

/Newswatch May 6_1991_Pg 1.jpeg)

/Newswatch May 6_1991_Pg 16.jpeg)